Learn more about higher education with this IndyPL reading list.

Learn more about higher education with this IndyPL reading list.

View reading list

The Statewide Decline in College-Going Rate

In 2010, 66 percent of graduating Indiana high schoolers chose to pursue some form of post-secondary education. This includes traditional four-year degrees, two-year associate’s programs, and one-year certificates. By 2020 that share had declined to just 53 percent–the lowest number on record in at least a generation. The COVID-19 pandemic impacted college-going rates in 2020, but the decline precedes that crisis. The college-going rate has declined each year since 2015. If trends from 2016 to 2019 had continued without the pandemic, the state’s college-going rate would still be an estimated 56 percent.The share of graduating high school students choosing college declined by 13 points in the last decade

Statewide College-Going Rates: 2010 – 2020

Male high school students are far behind female students in choosing to attend college

Statewide College-Going Rate by Gender: 2010 - 2020

Black students felt the largest decline in college-going rate compared to other racial and ethnic groups

Statewide College-Going Rate by Race & Ethnicity: 2010 – 2020

Students on the Federal Free or Reduced-Price Lunch Program had a steep decline in college enrollment

Statewide College-Going Rate by Socioeconomic Status: 2010 – 2020

Students in the 21st Century Scholars Program have a 30-point college-going advantage compared to students not in the program

Statewide College-Going Rate by 21st Century Scholars Status: 2010 – 2020

Declining College-Going Rate in Central Indiana

One positive trend for Central Indiana is that the region did not have as steep a decline in the college-going rate compared to the state as a whole. The Indianapolis metro area had a 12-point decline in college-going while the state experienced a 13-point decline. That difference may seem trivial, but a single percentage point in this measure represents over 250 high school students. Additionally, there were seven metro areas around the state with larger declines than Indianapolis. It should be noted here that no metro areas experienced an overall increase in the college-going rate, all declined by at least 7 points.The Indianapolis Metro Area had a larger decline in college-going rate than six of the state’s fourteen metro areas

Change in College-Going rate by Metro Area: 2010 - 2020

Marion County was among the six Central Indiana counties with a larger decline in college-going rate than the state overall

Change in College-Going Rate Relative to Statewide Shift: 2010 - 2020

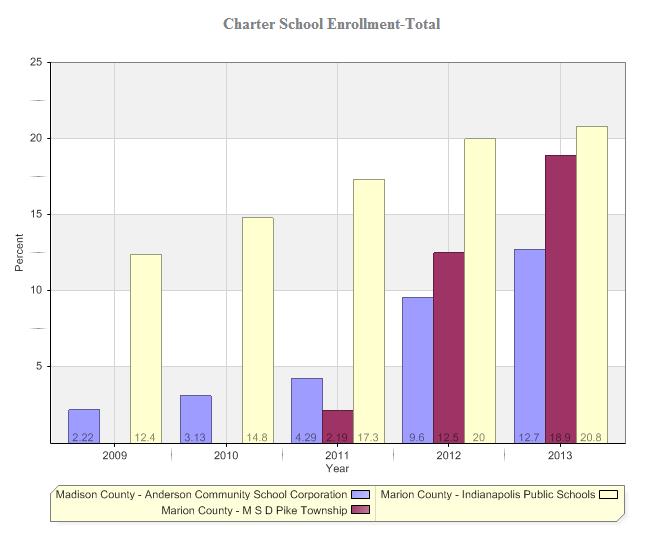

Trends in Central Indiana School Corporations

The story of college-going rates among school corporations in Central Indiana is one of income and affluence. A few exceptions exist, but the general trend is higher income and more educated communities produce a higher share of college-going students while lower income and less educated communities produce a lower share. Despite all the downward trends in overall college-going rate mentioned in previous sections, this relationship persisted between 2010 and 2020. For this section of our article, we use the U.S. Census Bureau’s geographic school district units to combine income and education data with the Commission for Higher Education’s college-going numbers. School “corporations” and school “districts” are used interchangeably throughout as they have the same meaning in our data. Analysis of school corporation data only includes public school corporations with geographic-based student bodies. All other sections of this report include private and charter schools as well. Some corporations only have one high school (e.g. Anderson Community School Corporation), others have multiple (Indianapolis Public Schools, for example). In 2010, school districts with the highest college-going rates were clustered in higher-income, highly educated suburban communities. In all but two of the top ten districts for college-going rates, the area median household income was higher than the metro area ($53,085 in 2010). Additionally, all but three districts also had a higher bachelor’s degree attainment rate than the metro area (31 percent in 2010). The only Marion County district to make the top ten—Washington Township—was significantly more educated and higher income than the county as a whole.Higher income and more educated school districts have higher shares of high schoolers choosing college

School districts with the ten highest college-going rates in 2010

The relationships between income, education, and college-going rates persisted through 2020

School districts with the ten highest college-going rates in 2020

Four Marion County School Districts were among those with the largest declines in college-going rates

School districts with the ten largest college-going rate declines between 2010 and 2020

College-Going Rate at IPS Schools peaked at 58% in 2014 and has since sunk to 31% in 2020

College-Going Rate at IPS Schools: 2010 - 2020

All Indianapolis Metropolitan School Districts had College-Going Rate Declines since 2010

College-Going Rate at Indianapolis Metropolitan School Districts: 2010-2020

College-Going Rates in Central Indiana High Schools

While the relationships between area income, bachelor’s degree attainment, and college-going rates at school districts seems clear at first glance, it’s always important to look for relationships between variables at the lowest level of the data hierarchy if possible. Sometimes trends at a higher level of a data structure (school districts or counties) can be different when moving further down the hierarchy (schools, in this case). The Commission for Higher Education publishes detailed statistics for many schools in the Indianapolis metro area on important variables that might be related to college-going rates. Our primary goal at this point in the analysis is to understand which factors influence a school’s college-going rate the most. In other words, what makes a school more likely to send students to college? To answer this question, we looked at data on all high schools in the Indianapolis metro area that met several criteria:- Schools that serve traditional high school-going populations. This means that organizations like career centers, juvenile correctional facilities, and schools for students with unique circumstances (e.g. Indiana School for the Deaf) were excluded from the data set.

- Schools with at least 10 students in their graduating class in 2020. Class sizes smaller than this produce college-going rates that can skew overall averages and trends and were excluded from the analysis.

- Schools that had valid data reported to the Commission on variables potentially related to college-going rates. Not all schools reported data on every variable collected by the Commission. Some did not because of privacy concerns, others because of very small subpopulation numbers.

- The percentage of graduating students on the Federal Free or Reduced-Price Lunch Program. This program is based on the student’s household income, which provides a good proxy for average economic resources of a graduating class.

- The percentage of graduating students receiving honors diplomas. Honors diplomas demonstrate the share of a graduating class that is either “high-achieving” or has access to resources allowing them to complete a higher-level diploma program.

- The percentage of graduating students who were white. Since not all schools in the dataset reported data for every racial or ethnic group, we used the white share of the graduating class, which was reported for every school. Some schools’ student bodies are so predominantly white that they keep race data protected for other groups as those populations are very small.

- The percentage of graduating students who participated in the 21st Century Scholars Program. This state-run program gives participating students full four-year tuition at public Indiana colleges if they meet certain income and academic standards. This measure gives us an estimate of the share of graduating students being provided financial help to attend college.

Schools with high rates of honors diplomas are most likely to have high college-going rates

Schools with the ten highest shares of students receiving honors diplomas, 2020

Not all overwhelmingly white graduating classes have high college-going rates

Ten Central Indiana Schools with 90% white graduating classes and below average college-going rates

View college-going rates for all Central Indiana high schools in our dataset

Full dataset can be downloaded by clicking "Get the Data" below