Tiny budget, big results: How SAVI helps create better public-health outcomes

Our Partner

Marion County Department of Public HealthThe Challenge

The Marion County Public Health Department has limited resources to fight the spread of infectious diseases.

The Solution

Melissa Titus uses SAVI to pinpoint the city’s most vulnerable areas—and then multiply the power of data through storytelling.

The Process

Disease can spread in countless ways, but the tools and money to fight it are limited.

If your job is to figure out which preventative measures will prove most effective, it’s important to make the most of your resources.

Few tools pack as much punch as SAVI, according to Melissa Titus.

Titus is an acute infectious diseases epidemiologist with the Marion County Public Health Department. In that role, she spends a lot of time “getting data from different sources to figure out where we can use our tiny budget to make the biggest difference.”

Recently, for example, she needed to know the percentage of households by census tract that didn’t have a vehicle.

“It’s beautiful. And it used SAVI data. I don’t have any clue where I could have found that information anywhere else.”

Melissa Titus

Marion County Department of Public Health

She needed the data because the department was creating a community health assessment—that is, a report published periodically that “looks at the health of the community to see if we have our priorities set correctly.”

“One portion of the assessment was, What kind of access do people have to health care?” Titus says. “Do they have insurance? Do they have a way to get to the services? We put it all into a report that can be used by people who make decisions in the health department, and in city government, on how to make the county healthier and more welcoming for businesses that want to locate here. But mostly for the health of our citizens.”

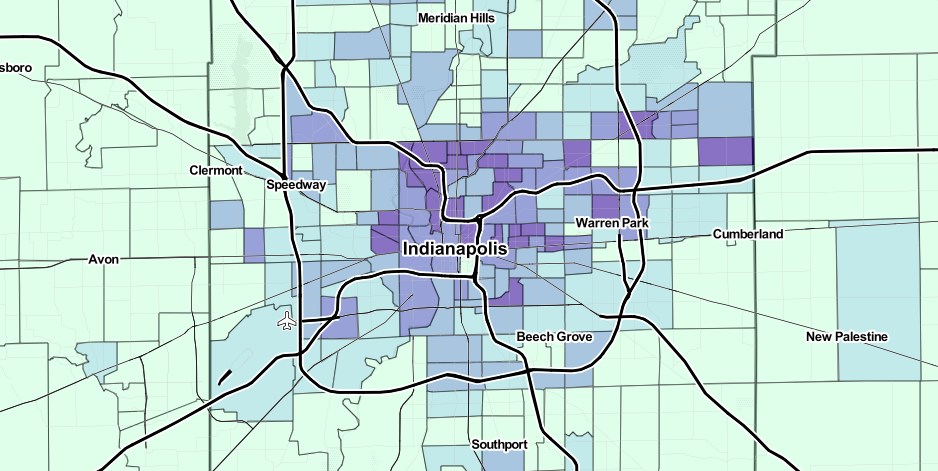

Titus was responsible for the portion of the assessment that analyzed ease of access to healthcare. “So I wanted to know, what populations don’t have access to vehicles but are near a bus line?” she says. “We went to SAVI, found the data, pulled it down, added the bus lines to the map, and figured out where there are gaps—areas where people don’t have cars and aren’t near a bus stop.

“And then I had our GIS people make a new map focused on just the area I wanted. It’s beautiful. And it used SAVI data. I don’t have any clue where I could have found that information anywhere else.”

Titus has taken a SAVI training class but describes her proficiency level as beginner. Even so, she uses SAVI data to inform nearly every report that she writes. She says that, for people new to SAVI or looking to improve their skills, the data stories are a great place to begin.

“If you start with one of the stories, you see how they’ve integrated data into telling a story, so that the data isn’t the most important thing,” she says. “The story of changing neighborhoods—that’s a beautiful one. When you start with stories, you understand how the data can be used to help with an argument.”

Titus is helping spread the word about SAVI—and helping stop the spread of infectious diseases—through community meetings across the county. The department inserts community profiles drawn from SAVI into its presentations. The profiles include data about median family income, median age, people living in poverty, and much more.

“We don’t have to do anything to the profiles to add them to our presentation,” Titus says. “That helps small communities go out and look for grants that will help pay for things that will make their health better. And putting that kind of knowledge in people’s hands is how we will make a difference in public health.”