In our analysis of Indianapolis’ changing neighborhoods, we found that this area lost 4,000 residents between 1970 and 1980. Its population has begun to grow modestly, but the demographic makeup has changed. In 1970, the neighborhood was almost entirely black, the growth of IUPUI’s campus and the general demographic trends of downtown Indianapolis have made this neighborhood increasingly white, college-educated, and populated with young adults.

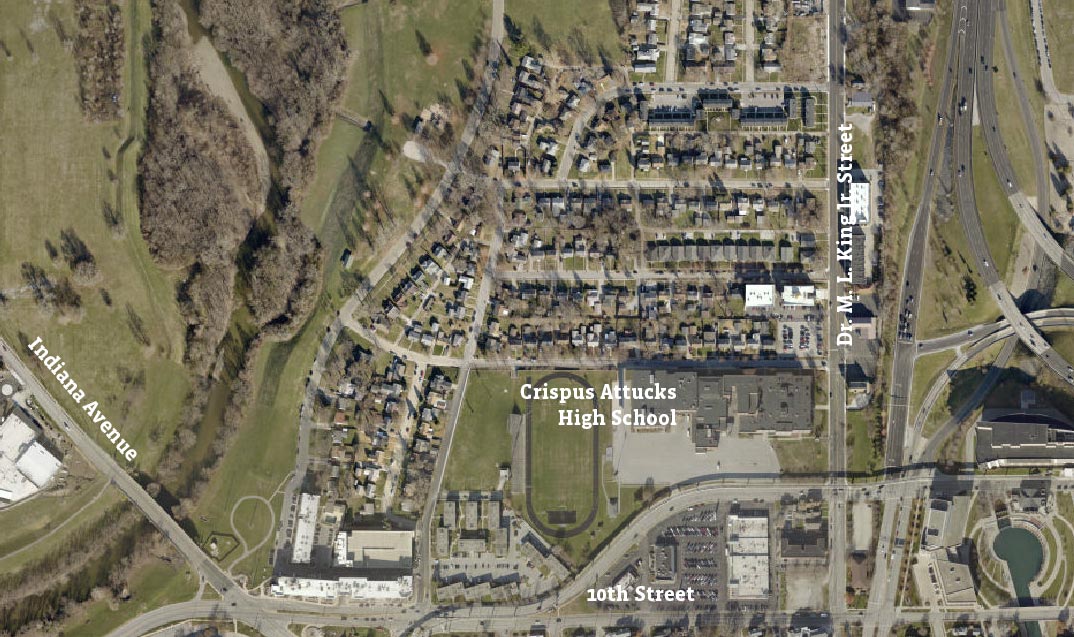

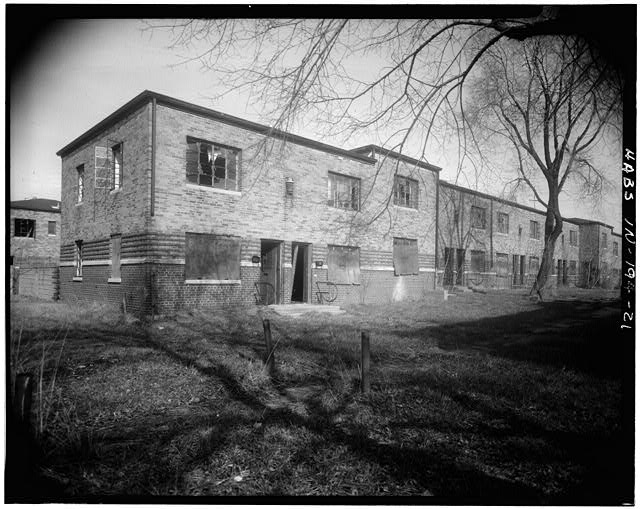

To understand these changes, we examine three smaller neighborhoods within this area more closely: Lockefield Gardens, Ransom Place, and the neighborhood around Crispus Attucks High School, once known as Pat Ward’s Bottom. Lockefield Gardens was a federal public housing project that served as an early model for future developments, but was eventually closed in 1976. It is now listed on the National Historic Register and has been redeveloped and partially preserved. Ransom Place is a late 19th-century historically black neighborhood that experienced significant decline by the 1980s. Since then, its preservation and redevelopment has contributed to population growth in this area. The neighborhood surrounding Crispus Attucks was densely developed with small urban lots by the 1930s. However, in the 1950s the area was completely redeveloped with modest (about 1,000 square feet), suburban homes. Recently, since 2010, new apartments have been constructed in this area that appeal to IUPUI students and professionals.

Lockefield Gardens

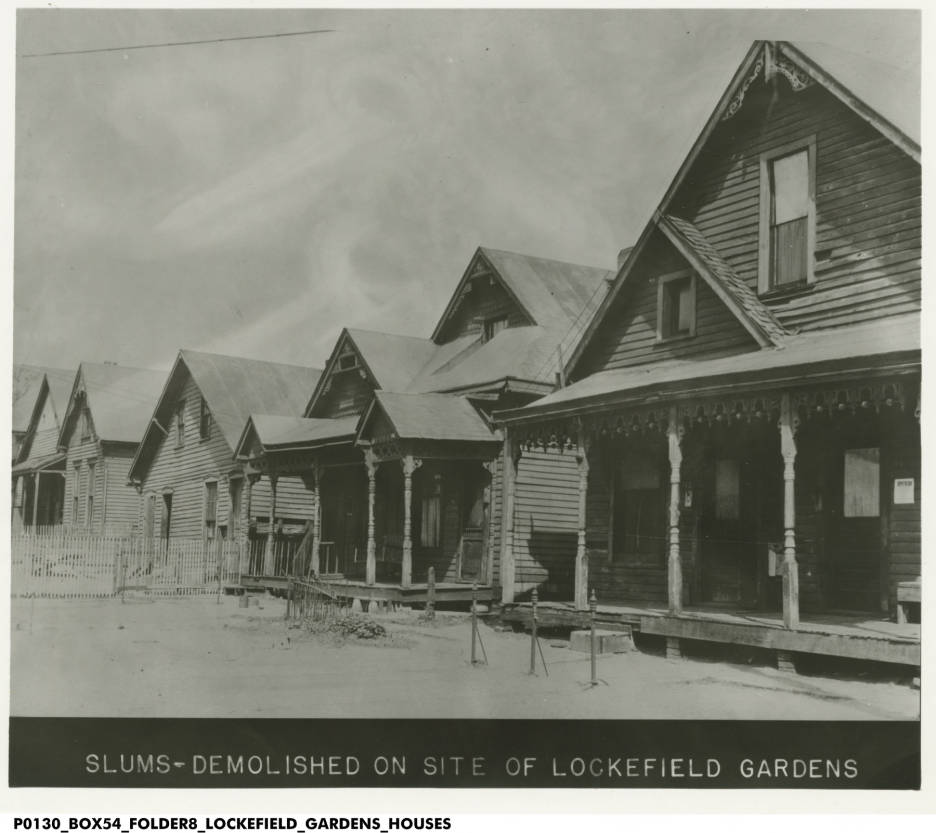

Lockefield Gardens was one of the nation’s first federally funded public housing projects. The project was funded through a “New Deal” program in 1934 and completed in 1938. Lockefield provided much-needed quality housing to black residents, many of whom were living in sub-standard housing. According the to Historic American Buildings Survey, “Lockefield was part of the first involvement of the Federal Government in providing low cost housing for the poorest urban Americans.”

In The Indianapolis Story, Emma Lou Thornborough of the Indiana Historical Society gives this account of substandard housing in black neighborhoods.

“The influx of Negro workers during the war years created a crisis in housing in older parts of the city. In 1942 the president of a local of the United Automobile Workers at the National Malleable Company, which included several hundred black members, reported that most of them were living “practically out of doors” in makeshift quarters. Even though they were earning good wages, rental property was not available to them. Throughout the war there were complaints of lack of housing and exorbitant rents for such substandard units as were available.”

Their designs, based on previous models by Henry Wright, were inspired by Europe’s International Style. Three quarters of the site was retained for greenspace, and the residences were positioned at an angle to provide sunny, south-facing windows in all units.

According to The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, rents were around $30 per month (equivalent to about $520 in 2018). The development was innovative in its inclusion of mixed uses and what we now call “wrap-around services”. A public elementary school was incorporated into the project, as well as retail space.

The closure of Lockefield probably explains most of the migration of 4,000 black residents out of this neighborhood. Lockefield had 798 units, which could have easily housed about 2,000 residents.

Census data can’t tell us where black residents moved to after leaving this neighborhood, but huge increases in black population in older northeastern and northwestern suburbs suggest that many black families left the city’s core for these 1950s and 1960s suburban neighborhoods. When these neighborhoods were developed, they were all-white. But by 1980, many neighborhoods northwest of downtown, along Lafayette Road, had substantial black populations, as did many neighborhoods in parts of Warren and Lawrence Townships.

Project A

Scroll through the images to see the results of Indianapolis' first slum clearance project, begun in 1948.Pat Ward’s Bottom

Redevelopment Near Crispus Attucks

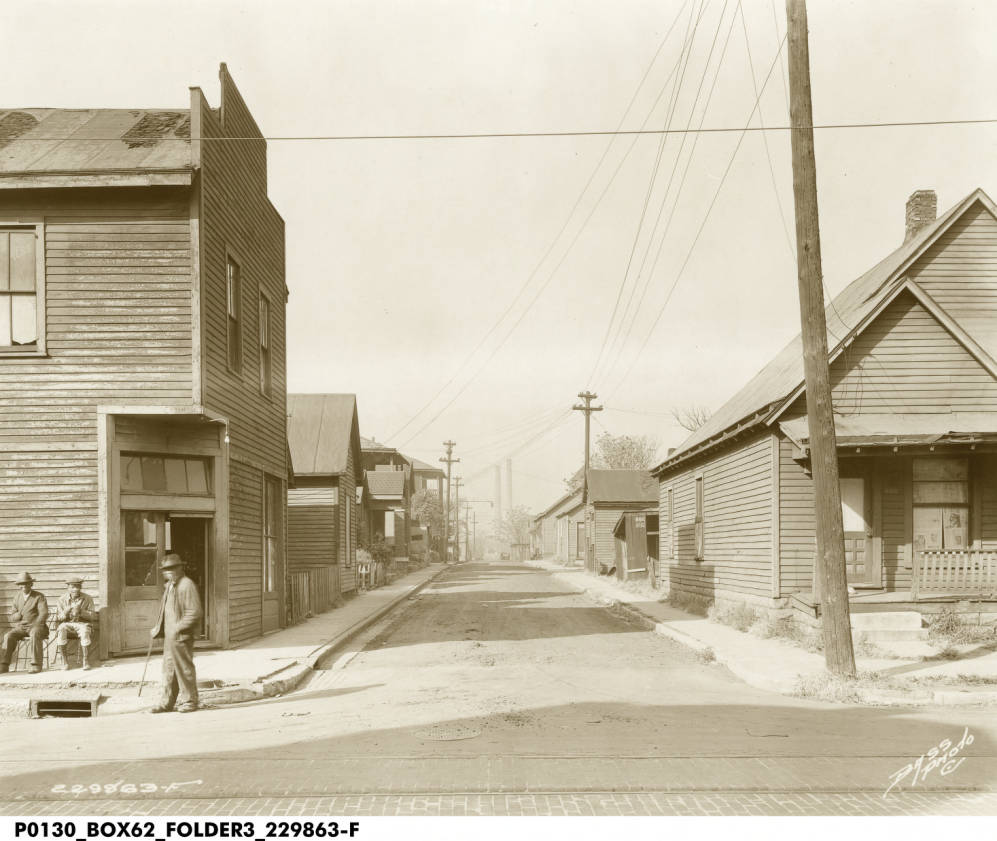

In the 1930s, the neighborhood around Crispus Attucks High School, known as Pat Ward’s Bottom, was densely populated by black families. Lots were small and homes were densely packed together.

However, in 1945, state legislation cleared the way for the neighborhood to be redeveloped. According to Indiana Historical Societ’ys Flanner House archives, “the Indiana Redevelopment Act established a plan for ridding cities of blighted or slum areas and redeveloping those areas.”

The Indianapolis Redevelopment Commission chose this neighborhood as the site of its first slum clearance initiative. Some residents were concerned that “dislocation would leave them homeless,” according to the Flanner House archives. Still, demolition began in 1948.

Clarence Wood, a black Indianapolis resident who worked with Flanner House to build homes in the area, said that before redevelopment, the area was “a complete slum… The houses were deteriorated,” according to an oral history from Indiana University and the Indiana Historical Society. Housing options limited black residents, according to Wood. “It was very difficult at the time. And you couldn’t buy a new house. There was no place you could buy a lot or anything like that. This is all black people in Indianapolis.”

Flanner House Homes made new housing available to black residents. According to Wood, by paying $300 down and working about 1,200 hours, a family could earn about $3,600 of equity in a home. Wood’s home was worth about $12,000 when it was finished in the 1950s.

Decline and Redevelopment in Ransom Place

Scroll through the images to see Ransom Place in 1937, 1986, and 2017.Preservation and Infill Development in Ransom Place

After losing 4,000 residents, the census tract containing Ransom Place, Lockfield Gardens, and Pat Ward’s Bottom began to slowly gain population again after 1980. Some new residents were attracted by preserved housing and infill development in the historic Ransom Place neighborhood.

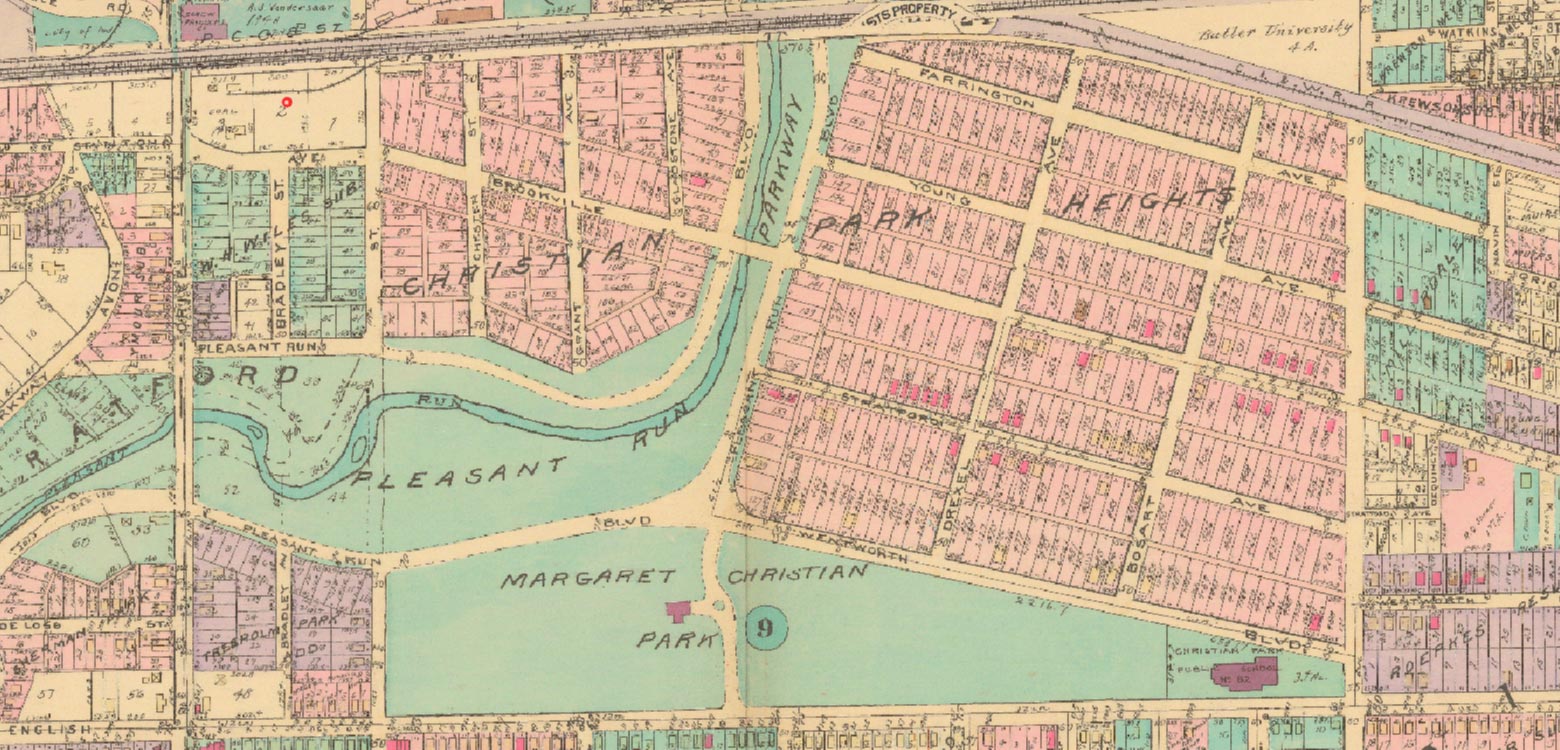

Ransom Place was first established as a black neighborhood in the 1890s. This small neighborhood was, like the rest of the area, densely populated with households in small cottages. In the middle of the 20th century, as IUPUI was established and expanded, commercial areas encroached on the neighborhood. As a result, Ransom Place began to decline. By the 1980s, vacancy and abondment had reduced both the population and housing stock.

The neighborhood was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992 and designated by Indianapolis as a historic district in 1998. Since then it has benefited from repaired historic homes and the construction of new homes on previously vacant lots. In 1986, Paca Street, the neighborhood’s western boundary, was almost entirely vacant lots. Between 1996 and 1997, 22 new homes were built on the east side of Paca Street. Because these homes were built before Indianapolis designated Ransom Place as a historic district, they were not required to adhere to historic design guidelines. (The city’s historic district has stricter design guidelines than are required under the National Register, and this street actually falls outside the bounds of the national historic site.) Still, the cross-gabled homes somewhat match the nearby historic cottages in style and site layout.

Demographic Changes Since 1970

Since the preservation and redevelopment of Lockefield Gardens and Ransom Place, black residents have moved away from this area, while white, college-educated, young adults have moved in.

In 1970, one percent of the neighborhood was white. In 2016, 38 percent of the neighborhood was white. The availabilty of more housing choices for black residents, as well as the growth of IUPUI, may have contributed to this change.

About one in seven residents were between 20 and 34 years old in 1970. By 2016, over half the neighborhood were in that age group. The neighborhood was less college-educated than the Indianapolis region as a whole in 1970; just two percent of the neighborhood population had a bachelor’s degree, compared to ten percent of the region’s population. But by 2016, 43 percent of the neighborhood had a bachelor’s degree, more than the regional average.

After falling from 5,173 residents in 1970 to 1,209 residents in 1980, the population has grown moderately. In 2016, 2,355 residents lived in the neighborhood. The neighborhood has grown about two percent per year since 1980, outpacing the regional trend.

This historically black neighborhood has been largely shaped by the mid-twentieth century forces of blight-remediation and slum clearance. These changes have been controversial. While some parts of this neighborhood were marked by genuinely bad living conditions (often lacking indoor plumbing), exorbitant rents, and absantee landlords, the effect of the displacement of black residents and culture has been dramatic. In the last five decades the area has become more and more demographically influenced by the urban campus at its door step, while preservationists have worked to preserve markers of its heritage.

See How Your Neighborhood Has Changed

Find more interactive content from our series on neighborhood change.

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.