Equity in Criminal Prosecutions: Analyzing Case Filings from the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office

A special thank you to the Kheprw Institute, who was a research partner on this initiative. It was funded through the Catalyst Grant Program, a collaboration of the Microsoft Justice Reform Initiative and the Urban Institute.

Additional thanks to the Vera Institute of Justice and the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office for assisting in accessing and understanding the data.

Introduction

The Kheprw Institute and The Polis Center are partnering to better understand the criminal justice system in Marion County and investigate potential disparities. This report is the next step in several prior analyses and reports examining the local criminal justice system.

Previous research from the Polis Center estimated that Black residents of Marion County were 2.7 times more likely to be jailed than their white counterparts in 2018 and 4.4 times more likely to be imprisoned in 2016. Significant progress has been made to narrow the racial gaps in both the prison and jail population, but that has slowed in recent years. Building off this research, Polis examined more than 283,000 bookings in Marion County jails between 2013 and 2021 to understand the jail population. Despite a significant drop in the jail population during the COVID-19 pandemic, jail levels have mostly returned to pre-pandemic numbers.

This report moves that prior work forward adding a new layer of data from the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office (MCPO). Our core dataset in this report covers cases filed by the Prosecutor’s Office against defendants between 1/1/2017 and 8/23/22. We first provide an overview of activity from the Prosecutor’s Office during this time period, we then analyze the data with respect to disparities in race/ethnicity, age, and sex of the defendants. In addition, we attempt to merge Marion County Jail bookings data with prosecution data from the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office to look into instances where individuals may be booked in the jail, but no charges are filed. The Polis Center plans to expand our partnerships around data sharing and linking between datasets to explore multidimensional criminal justice issues like this moving forward.

Case Filings Overview

Key Takeaways: The number of cases filed per month by MCPO has dropped significantly compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. Case filing rates have dropped at similar rates for both white and Black defendants

Case Filings by Defendant Subgroup

Key takeaways: Black defendants are significantly overrepresented in case filings compared to the Black share of the Marion County population. Over half of all cases filed by MCPO are against Black defendants while Black adults make up just 27% of the Marion County population.

Case Outcomes by Race/Ethnicity

Key takeaways: A higher percentage of cases filed against Black defendants have all charges dismissed than cases filed against white defendants. This finding highlighted challenging gaps in our dataset that prevent us from understanding why this is happening.

Spotlight: Reform efforts by MCPO

Key takeaways: The decision by MCPO to no longer prosecute low-level marijuana possession when it is the only or most serious charge in a case has resulted in a significant reduction in case filings against both Black and white defendants. However, a small number of these cases are still being filed, mostly against Black defendants. Additionally, Driving While Suspended case filings have dropped significantly since the spring of 2020, indicating a shift in prosecutorial priorities and resource allocation.

Next steps: Linking prosecution and jail bookings data

Key Takeaways: Less than 2% of people booked in the Marion County jail each year have only “placeholder” charges from their arrest but never have formal charges filed by MCPO. This percentage has declined to around 0.1% of those booked in the jail in more recent years.

Understanding our datasets

Our Core Dataset

Our core dataset includes 143,460 unique cases filed by the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office (MCPO) against defendants in the county between 1/1/2017 and 8/23/22. Some cases were still “open” at the time of our data request. For instances in this report where we examined the number of case filings, all cases were included regardless of their status. For sections of the report analyzing the outcomes of cases, we only include “closed” cases, as these are the only cases where an outcome has been determined.

There were a number of key fields included in the dataset we received from MCPO:

- Case Number

- Case Status (e.g., Open, Closed)

- Case Filing Date

- Offense Name

- Offense Level (e.g., Level 2 Felony, Class B Misdemeanor)

- Offense Disposition (i.e., charge outcome)

- Lead Charge (i.e., most serious charge in the case)

- Offender Name

- Offender Date of Birth

- Offender Race

- Offender Sex

However, the dataset from MCPO does not include all relevant fields that one might want to use to understand the criminal prosecution system and identify potential disparities. For example, there are some instances where other key data is missing that could help answer questions.

- Detailed information on Offense Disposition (e.g., did the defendant enter a plea agreement?)

- Offender Address

- Offense Disposition Date

- Detailed information on cases received but declined to be filed by MCPO

- Offender poverty status or homelessness status

- Quality of evidence or quality of witnesses

- Quality of legal representation

Our Secondary Dataset

In addition to our analysis of the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office data, we also looked at publicly available data on bookings in the Marion County jail system. The Kheprw Institute created a tool to download and analyze booking data, which was merged with the MCPO dataset to look at instances where people were booked in the jail but no charges were filed.

Cases filed by Marion County Prosecutor’s Office

The dataset provided to us all cases filed by the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office from the beginning of 2017 through most of 2022. The number of cases filed by the prosecutor per year has decreased significantly during these years. The average number of cases filed by the prosecutor per month between 2017 and 2019 was around 2,500. From 2020 through 2022, the average number of cases filed per month was just 1,600.

It’s clear that the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on the frequency of case filings from MCPO. The decline in case filings coincided roughly with the first reported instance of coronavirus in Indianapolis (March 6, 2020), represented by a red shaded area on the chart to the left. As we noted in our previous research into the Marion County jail population, local criminal justice officials, including the Prosecutor’s Office, worked to reduce jail populations during this time to manage the spread of the virus.

The decline in cases, however, does not appear to be only a function of the pandemic, as cases filed by the prosecutor did not return to pre-pandemic levels in 2021 or 2022. The pandemic may have been the impetus for the initial drop in case levels, but a more longstanding change in approach by the prosecutor’s office appears to have occurred over the past few years. It’s also possible that Marion County continues to face challenges similar to many jurisdictions around the country related to strained resources, overloaded court systems, and mounting backlogs that have led to fewer cases being filed.

Unfortunately, our data does not include the case disposition (i.e., judgement) date, only the date it was filed. This means we cannot be certain that case processing times have increased in Marion County since the beginning of the pandemic. Whatever the reasons may be, case filing levels have remained substantially lower in 2021 and 2022 compared to pre-pandemic years.

Cases are composed of charges

Each case brought by the prosecutor includes 2.2 unique charges on average, meaning that for case filed, a defendant is usually charged with more than one offense. For example, a prosecutor may file a case that includes both “Operating a Vehicle While Intoxicated Endangering a Person” and “Driving while Suspended” as individual offenses charged.

The mix of charges in our dataset included 604 unique offense names, like “Possession of Cocaine” or “Criminal Trespass”. Some offenses—like “Driving While Suspended”—were charged tens of thousands of times while others—like “Dealing in a Sawed-off Shotgun”—were charged just once.

No single offense makes up more than seven percent of all charges filed by MCPO. The most frequently filed charge is for "Driving While Suspended", followed by "Theft", then "Domestic Battery". The chart to the left shows the top twenty most frequently charged offenses by MCPO during our five-year window. The overwhelming majority of offenses make up less than one percent of all charges filed.

A table with over 600 unique values can be difficult to visualize or summarize. So, we placed each of these offenses in one of eighteen exclusive categories. These categories were created in consultation with our partners at the Vera Institute for Justice and used the Indiana Criminal Code for guidance in some instances. The categories were created for analysis purposes and may not exactly mirror the categories used by MCPO internally. In the "How we categorized charges" section below, you can view a detailed description of how each charge was placed into a category.

How we categorized charges

A description of each of the eighteen categories we created to group charges is below along with the most common charges in each group. You can also view the full list of offense names and how they were categorized here.

1) Vehicle

- Charges where the core of the offense involves operation of a vehicle, driver’s license issues, or vehicle registration issues

- Does not include DUI

- Most common charges in this category: “Driving while Suspended,” “Operating a Motor Vehicle Without Ever Receiving a License,” “Leaving the scene of an accident”

2) Drug Possession

- Charges based on the possession of an illicit drug or drug paraphernalia

- Does not include drug dealing or manufacturing

- Most common charges in this category: “Possession of Marijuana,” “Possession of Paraphernalia,” “Possession of a Narcotic Drug”

3) Violent Crime

- Charges for violent acts intended for bodily harm of another person

- Does not include Murder, Attempted Murder, Conspiracy to Attempt Murder, Voluntary Manslaughter, Domestic Violence charges, or Sexual Violence charges. These charges are split out into their own categories.

- Most common charges in this category: “Battery Resulting in Bodily Injury,” “Criminal Confinement,” and “Strangulation”

4) Property

- Charges where the offender illegally took, destroyed, or attempted to take or destroy another’s property, or illegally occupied another’s property.

- Most common charges in this category: “Theft,” “Criminal Trespass,” and “Criminal Mischief”.

5) DUI (Driving Under the Influence)

- Charges for operating a motor vehicle while impaired by the usage of alcholor or illicit drugs

- Most common charges in this category: "Operating a Vehicle While Intoxicated Endangering a Person", "Operating a Vehicle While Intoxicated", "Operating a Vehicle with an ACE of .15 or More"

6) Obstructing Justice

- Charges where the offender was deemed to have been attempting to, or succeeding in, obstructing a legal proceeding or the actions of a law enforcement officer or representative of the judicial system

- Most common charges in this category: “Resisting Law Enforcement,” “Interference with the Reporting of a Crime,” and “False Identity Statement”

7) Domestic Violence

- Charges of interpersonal violence between partners in an intimate relationship

- Most common charges in this category: “Domestic Battery,” “Domestic Battery Resulting in Moderate Bodily Injury,” “Domestic Battery by Means of a Deadly Weapon”

8) Public Order

- Charges where the offender was deemed to be disturbing the peace or acting improperly in public

- Most common charges in this category: “Public Intoxication,” “Disorderly Conduct,” and “Public Nudity”

9) Intimidation & Personal Privacy

- Charges where the offender was deemed to have threatened the safety or invade the personal space of another person

- Most common charges in this category: “Intimidation,” “Invasion of Privacy,” and “Harassment”

10) Drug Dealing

- Charges where the offender was deemed to be manufacturing or selling illicit drugs

- Most common charges in this category: “Dealing in Marijuana,” “Dealing in a Narcotic Drug,” and “Dealing in Methamphetamine”

11) Weapons

- Charges based on the improper possession of guns or other weapons

- Does not include the usage of weapons, only their possession

- Most common charges in this category: “Carrying a Handgun without a license,” “Unlawful Possession of a Firearm by a Domestic Batterer,” and “Dangerous Possession of a Firearm”

12) Fraud

- Charges where the offender attempted to or succeeding in deceiving or defrauding another person or institution

- Most common charges in this category: "Forgery", "Synthetic Identity Deception", and "Fraud"

13) Sexual Misconduct

- Charges based on improper sexual contact or attempts at improper sexual contact/conduct

- Includes improper sexual acts against children

- Most common charges in this category: “Child Molesting,” “Failure to Register as a Sex or Violent Offender,” “Possession of Child Pornography”

14) Alcohol

- Charges for the improper possession, usage, or sale of alcohol

- Does not include DUI or Public Intoxication

- Most common charges include “Illegal Possession of an Alcoholic Beverage,” “Illegal Consumption of an Alcoholic Beverage,” and “Minor in Possession of Alcohol”

15) Child Abuse

- Charges for the mistreatment of a minor but not sexual in nature (sexual child abuse is included in the “Sexual Misconduct” category)

- Most common charges in this category: “Neglect of a Dependent,” “Neglect of a Dependent Resulting in a Bodily Injury,” and “Dissemination of Matter Harmful to Minors”

16) Other

- Charges that are infrequent and do not fit neatly into one of our defined categories

- Most common charges in this category: “Cruelty to an animal,” “Refusing to Leave Emergency Incident Area,” and “Official Misconduct”

17) Murder/Voluntary Manslaughter

- Charges for intentionally killing or attempting to intentionally kill another human being

- Does not include unintentional killings like “Involuntary Manslaughter,” which is in the “Violent Crime” section

- Charges in this category: “Murder,” “Attempted Murder,” “Voluntary Manslaughter,” “Conspiracy to Commit Murder”

18) Prostitution/Sex Work

- Charges where the offender was deemed to have performed or solicited illegal sex work

- Charges in this category: “Prostitution,” “Making an Unlawful Proposition,” “Promoting Prostitution,” and “Patronizing a Prostitute”

Offenses categorized by SAVI as “Vehicle” are the most commonly filed charges by the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office, representing nearly 18 percent of all charges filed between January 2017 and August 2022. Vehicle charges are followed by Drug Possession and Violent Crime offenses, each making up over 14 percent of all charges respectively. It’s important to reiterate that multiple charges are usually filed together within a case and prosecutors do not generally think of charges outside of their containing case. However, it’s helpful to understand what kinds of charges are filed before delving into potential disparities by subgroup.

It’s also important to note that grouping offenses in different ways produces different answers to the question, “What is the most common charge category?” For example, if DUI and Vehicle charges were combined in one category, they would equal nearly 29 percent of all charges. However, some of these Vehicle charges are low level infractions like seatbelt violations, making them odd companions to “Operating a Vehicle While Intoxicated Endangering a Person”.

“Violent Crime” is separated from “Domestic Violence” and “Murder/Voluntary Manslaughter” in our categorization, but these categories could also be plausibly combined. If that were so, this new combined category would be the largest category with over 20 percent of all charges. Any grouping is inherently subjective, but our categories attempt to provide clarity into the prosecutor’s actions and are not intended to obscure the story.

Charges are filed at different levels

Offenses are also grouped by type and level. The three types of offenses in Indiana are felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions, with felonies generally considered as the most serious crimes. Within each type, offenses are ordered by level of their severity as determined by law. Felonies are ordered from Level 6 to Level 1, with 1 being the highest (or most severe) while misdemeanors are ordered from Class C to Class A, with A being the highest. Infractions are ordered from Class D to Class A, with A also being the highest.

Indiana's offense levels have changed over time

A very small percentage of charges in our dataset (less than 0.5%) were filed with the old offense level hierarchy (pre-2014) that had just four felony classes: Class A – Class D. That system was replaced with the data shown in the chart: Level 1 – Level 6. Offense can still be charged using the old system if the alleged crime was committed before 2014. For example, some child molesting cases do not surface until years after the abuse was committed. Given the very small number of charges that fit this situation, those charges have been excluded from analysis to avoid confusion.

Specific offenses can be charged at different types and levels based on the severity of the crime. In other words, the same offense will not have the same type and level each time it is charged. For example, “Possession of Marijuana” was sometimes charged as a Level 6 felony and other times as a Class A or B misdemeanor in this dataset, depending on the amount of drugs involved and other circumstances like if the defendant was growing marijuana, for example. The most common charge level for marijuana possession was a Class B misdemeanor, accounting for 74 percent of all marijuana possession charges.

Some offenses are always charged at the same level. “Attempted Murder” is always charged as a Level 1 felony. “Murder” is itself listed in its own category simply as “Felony Murder” to denote the highest level of severity in the legal hierarchy.

Class A misdemeanors (36%) and Level 6 felonies (27%) combined made up over 64 percent of all charges in our dataset. When ordering the offense levels from least to most severe, the distribution of charges form a distribution similar to a bell curve, with the most frequently charged offenses clustering around the midpoint of the legal hierarchy. Infractions make up around 5 percent of all charges filed and are generally low-level vehicle offenses like “Failure of an Occupant to Wear a Seatbelt” that can only result in fines, not jail time.

Cases can be categorized by their "lead" charge

The Marion County Prosecutor’s Office typically categorizes cases by the most serious offense charged. For example, a case might include three charges with the most serious (or highest offense level) being a Level 6 Felony Domestic Violence charge and the other two charges being lower-level misdemeanors. This case would be categorized as a “Domestic Violence” case because the “lead charge” (or most serious charge) was in the Domestic Violence category. Every case in our dataset had one charged marked as the “lead charge”, including in cases where multiple charges were filed at the same level.

The distribution of cases by their lead charge category largely mirrors the distribution of charges by category shown earlier with a few notable exceptions. Property cases are the most frequently filed case category, accounting for nearly 18 percent of all case filings. Property charges only account for 12 percent of all charges, but these charges are often the most serious in a case, like “Auto Theft”, for example.

Obstructing Justice offenses account for 6.5 percent of all charges but only 5.1 percent of cases have an Obstructing Justice charge as the most serious offense. The most common Obstructing Justice charge is “Resisting Law Enforcement”. Of cases that have “Resisting Law Enforcement” listed as one of the charges, 48 percent have it listed as the lead charge while the other 52 percent of cases list some other offense as the lead charge.

Some case categories had larger declines in filing rates than others. Vehicle, Drug Possession, and Property cases had the largest contribution to the decline in overall cases filed by the prosecutor. There were over 1,200 fewer cases filed per month in 2022 compared to 2017 and these three case categories accounted for nearly 70 percent of the decline. Nearly every category had a decline in cases filed between 2017 and 2022 with only Murder/Voluntary Manslaughter, Sexual Misconduct and Other categories showing an increase.

Policy action from MCPO like no longer prosecuting most low-level marijuana possession offenses and helping drivers get their suspended licenses reinstated contributed to the decline in Drug Possession and Vehicle cases. The impacts of these actions are explored in the “Reform Efforts” section near the end of this report.

Case Outcomes

The ultimate outcome of a case is more difficult to determine than the outcome of an individual charge. There is not an overall outcome listed with each case in the prosecutor’s data as some charges could be dismissed while others found guilty within a single case. To deal with this complexity and determine the overall outcome of each case, we created a hierarchy of three outcomes that considers the outcomes of each charge within the case.

The dataset we obtained included eight charge outcomes. To simplify the data for visualization, charge outcomes were grouped into one of three buckets: Dismissed, Guilty, and Not Guilty. The original charge outcomes and their associated groupings are listed below.

How we did this

There were eight charge outcomes listed in the MCPO dataset. These eight outcomes were simplified to three buckets: Guilty, Not Guilty, and Dismissed How each charge outcome mapped to these three buckets is below.

- Guilty (Conviction Merged) -> Guilty

- Guilty but Mentally Ill -> Guilty

- Guilty including plea by agreement -> Guilty

- Not Guilty -> Not Guilty

- Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity -> Not Guilty

- Vacated -> Not Guilty

- Dismissed -> Dismissed

- Pending -> Excluded from dataset. These charges were marked with both a “Closed” status and a “Pending” disposition. After communication with the prosecutor’s office, it was determined that these charges likely represented data errors in the MyCase system. Charges in this situation represented around 4 percent of all charges and their exclusion would not alter any conclusions drawn from this report.

Once charges within the case were categorized into each of the three available dispositions, the case overall was assigned one of three outcomes.

- Guilty: If any charge in the case was guilty, the entire case was considered “Guilty”

- Not Guilty: If no charges in the case were guilty, and at least one charge was not guilty, then the case was considered “Not Guilty”

- Dismissed: If all charges were dismissed then the case was considered “Dismissed”

Over 60 percent of all cases filed by MCPO between 2017 and 2022 ended with at least one guilty charge. Thirty-eight percent ended with all charges dismissed, and around one half of one percent ended with no guilty charges and at least one not guilty charge. A case ending in a “Not Guilty” status is extremely rare, likely because many cases that might end with a Not Guilty verdict do not go to trial or are dismissed by the prosecutor during the process.

In all years but one, the share of cases with at least one guilty charge was over 60 percent. Only 2019 broke trend, with 58 percent ending with this outcome. Case outcomes were not consistent, however, across offense levels. In general, the higher the offense level of the most serious charge in the case, the more likely the case is to end with at least one guilty charge. Of cases where the most serious charge was a misdemeanor, 50 percent end with at least one guilty charge. For those with a felony as the most serious offense, 74 end with at least one guilty charge. This does not mean that a more serious charge is always more likely to end in a guilty verdict. Rather, the existence of a serious charge within a case makes a defendant more likely to be convicted of the charges in the case.

MCPO does not generally think about things like “guilty rates” at the individual charge level, but rather considers the entirety of the case like shown above. Regardless, it’s helpful for the purposes of this analysis to compare outcomes at the charge level to outcomes at the case level. In contrast to cases, over two thirds of charges are dismissed, nearly a third are guilty, and less than one percent are not guilty.

While our dataset does not include information on plea deals, it's possible that the gap in guilty rates between charges and cases represents the common situation of a defendant pleading guilty to one charge in exchange for several other charges being dismissed.

Cases filed by MCPO by subgroup

Approximately 27 percent of Indianapolis (Marion County) residents over the age of 18 are Black, 9 percent are Hispanic or Latino, and 58 percent are White, Non-Hispanic. However, Black residents are significantly overrepresented in cases filed by the prosecutor. Of cases filed between 2017 and 2022, 50 percent were against Black defendants. Conversely, both White and Hispanic defendants were underrepresented compared to their share of the population.

This is not an uncommon situation across the country. Nationally, the Black population has long been significantly overrepresented at most levels of the criminal justice system. Overrepresentation of the Black population is also a common situation here in Marion County. Our previous report on the local jail population, found a similar overrepresentation of the Black community. Just like in case filings, over half of those in jail are Black compared to 27 percent of the population.

As demonstrated at the beginning of this report, there has been a sharp decline in total cases filed by the prosecutor since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. All major racial & ethnic groups in our dataset had significantly fewer cases filed per month in 2021 and 2022, compared to pre-pandemic years. However, there were some differences between groups in the magnitude of the decline.

Cases filed per month white defendants fell by 50 percent between 2017 and 2022 compared to a 44 percent drop for Black defendants. The largest decline in cases filed per month was among Hispanic defendants, who experienced a 76 percent drop between 2017 and 2022.

There are legitimate reasons to question the accuracy of case filing numbers for Hispanic defendants in our dataset, given their small sample size. For those interested, we've provided a deeper dive in the expandable section below. Regardless, it’s clear that Black defendants had the smallest drop in case filings.

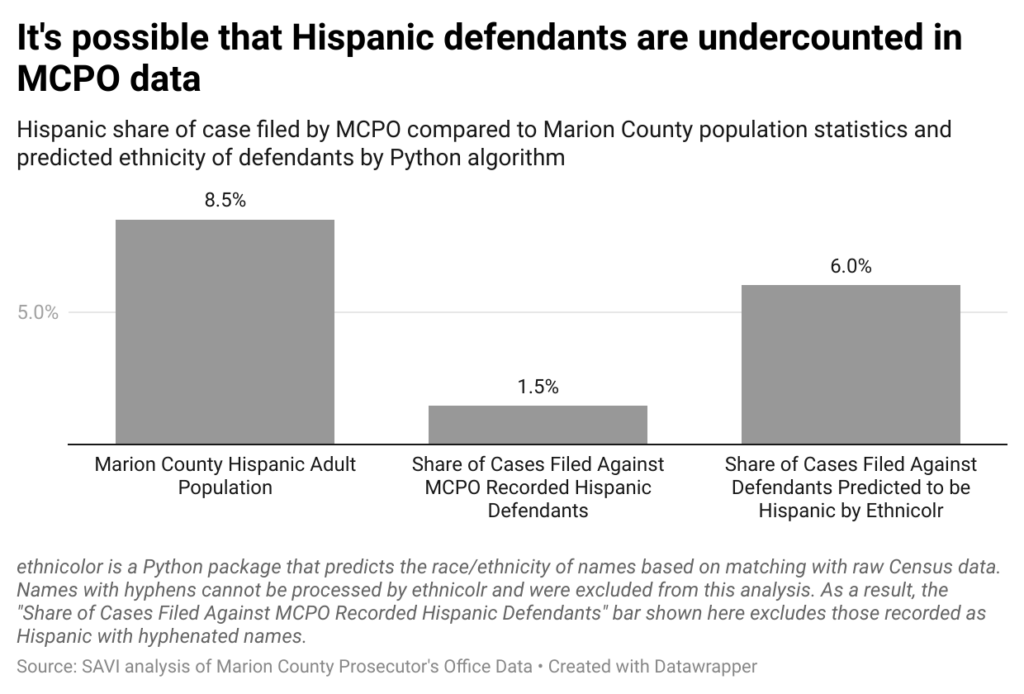

Hispanic defendants may be undercounted

The share of cases filed against Hispanic defendants in our dataset was just 2.7 percent, significantly lower than the Hispanic or Latino share of the Marion County adult population. While this may be accurate, it's also possible that data collection issues in the legal system have caused some Hispanic individuals to be coded as other races or ethnicities in the data.

Data quality related to Hispanic or Latino identities in the criminal justice system is an issue in many jurisdictions nationwide. Here in Marion County, jail administrators estimate that the jail population may be 10 percent Hispanic compared to the 5 percent recorded as Hispanic due to many being miscategorized as "White". These issues can stem from poor data collection practices but also from the complexities around defining and tracking ethnicity and race.

For example, the race and ethnicity listed with each defendant in our dataset comes from either the Officer’s Arrest Report for outright arrests or from the investigating detective’s screening packet for warrant arrests. According to MCPO, at no point in the process is the defendant asked to self-identify with a race or ethnicity. Rather, it is recorded based on the assumptions of the person documenting the arrest.

To investigate whether there may be race and ethnicity data errors in the prosecutor’s data, we employed a Python package recommended by the Vera Institute of Justice called "ethnicolr" designed to identify potential racial and ethnic mis-codings by scanning common names. The tool matched the first and last names of defendants in our dataset to names in raw U.S. Census data. Then, it predicted a race or ethnicity for each person based on how often their name was coded to each group in Census data.

Not all names from our MCPO dataset matched a name in the Census data. Any names with a hyphen cannot be processed by ehtnicolr, so were excluded. For those names that did match, the predicted share of Hispanic defendants was much higher than what was recorded in the MCPO data. Of those names that matched, just 1.5 percent were recorded as Hispanic in the prosecutor's data. However, over 6 percent of names that matched were predicted to be Hispanic according to how often names were identified with each race/ethnicity in the Census.

The names that were predicted to be Hispanic by the Census name-matching tool were given a 90% confidence rating, much higher than names predicted to be any other race/ethnicity in our data. While we can't be sure whether an undercount is happening, the results of this analysis suggest it may warrant further investigation of data collection practices in the local criminal justice system.

Case categories by race and ethnicity

The roots of inequity in the criminal justice system are well-documented and include many long-standing issues that extend beyond police, prosecutors, and courts. Our previous research report, The Cradle to Prison Pipeline in Indianapolis, highlighted how “Economic, racial, social, and educational inequities, all linked to a child’s neighborhood,” produce situations where people of color are more likely to get involved with the criminal justice system. Those factors also produce situations where people of one group are more likely to be charged with a specific offense compared to people in another group.

For example, Black Indianapolis residents are more likely to live in neighborhoods with lower median incomes and that were historically redlined. A more frequent police presence in these neighborhoods may lead to a disproportionate share of residents being arrested for offenses that are also happening in other neighborhoods but go unnoticed due to fewer police patrols. Additionally, the difficulties faced by certain populations—such as lack of citizenship among some Hispanic residents—can lead to specific offenses being charged that would be less likely among citizens.

Each dot in the chart to the left represents the share of cases that each specific offense category contributes to the overall mix of cases filed against defendants in each racial and ethnic group. For example, the “Drug Possession” line shows that a higher share of cases filed against white defendants (purple dots) have a Drug Possession lead charge compared to cases filed against Black (yellow dots) and cases filed against Hispanic defendants (grey dots.)

The clearest takeaway is that a majority of cases filed against Hispanic individuals are for Vehicle offenses. More specifically, 44 percent of all cases against Hispanic defendants are for not having a driver’s license. No other type of case comes close to making up that large of a share of cases for any racial or ethnic group. While data on the citizenship status of defendants was not within the scope of our dataset, it is possible that many of the charges were filed against those without documentation.

The Center for Migration Studies estimates that there are over 28,000 undocumented individuals living in Marion County, nearly 60% of which are of Hispanic origin. Indiana is one of many states where an unauthorized immigrant cannot receive a driver’s license, but a bill currently working through the Indiana General Assembly would change that. A recent study from Notre Dame’s Student Policy Network cited redirecting law enforcement resources from prosecuting this population for not having a license as one positive benefit of changing the law.

Case filings by age, sex, and race/ethnicity

National statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports database show that male defendants comprise over 70 percent of all people arrested nationwide. Violent offenses—such as homicide—are overwhelmingly committed by male offenders. Research from the U.S. Justice Department compiling crime statistics between 1980 and 2008 found that nearly 90 percent of all homicides were committed by male offenders. Here in Indianapolis, our review of data from the prosecutor’s office found similar patterns of male overrepresentation compared to general population statistics.

Of all cases brought by the prosecutor between 1/1/2017 and 8/23/22, 73 percent were filed against male defendants. Comparatively, just 47 percent of the adult population in Indianapolis is male. In addition, the share of cases brought against male defendants has been increasing in recent years. In 2017, 72 percent of cases filed by MCPO were against male defendants. By 2022, that share had risen to 77 percent of all cases.

In general, cases with a Property, Vehicle, or Drug Possession charge make up a higher share of cases filed against female defendants than male. Male defendants, on the other hand, have a higher share of cases filed against them with a Violent Crime, DUI, Domestic Violence, and Weapons lead charge. These numbers are in line with our report for the Indiana Domestic Violence Network, which found that 81 percent of Domestic Violence perpetrators are male and 71 percent of victims are female.

Only focusing on the case categories that are most often filed can overshadow some important differences in case filing rates among some less common case categories. Prostitution and Sex Work cases, for example, make up less than one half of one percent of all cases filed by MCPO. However, there were two times as many female defendants charged with a case in this category compared to male. This is similar to national statistics from FBI, which show two times as many females are arrested for prostitution-related offenses compared to men.

There is a stark contrast in who is charged for the specific offense types within this category. All of the cases for "Making an Unlawful Proposition" or "Patronizing a Prostitute" was filed against a male defendant. Comparatively, 97 percent of the cases for "Prostitution" were filed against a female defendant. As some organizations push to decriminalize sex work around the country, it's important to keep these statistics in mind.

The distribution of case filings is heavily clustered around early adulthood, as evidenced by the pie chart. Over 70 percent of all cases filed by MCPO were against defendants 39 years or younger. The age cohort with the largest number of case filings are defendants age 14-29, with 42 percent of cases. By contrast, just 3 percent of all case filings were against those age 60 or older.

A very small percentage of cases (0.4%) in our dataset were filed against someone under the age of 18. Juveniles can be charged as adults in Indiana if the prosecution files a motion in juvenile court that the defendant should be tried as an adult, or they can be directly filed in adult court. Certain offenses qualify for direct file into adult court including murder, rape, armed robbery, and kidnapping. The Indiana Criminal Justice Institute reported that over 80 percent of all juveniles charged as adults were results of direct file. Some community leaders in Indiana have recently pushed for eliminating the practice of directly filing juveniles into adult court, but those efforts have not gained traction in the state legislature.

While case filings were generally more frequent for younger defendants of all defendant identities in our dataset, combining race, sex, and age does show some differences within subgroups.

Young males make up a larger share of cases filed against Black and Hispanic defendants compared to white. Males under the age of 29 make up 34 percent of all case filings against Black defendants and 35 percent of all case filings against Hispanic defendants. Comparatively, only 26 percent of all case filings against white defendants come from males age 29 or younger.

For female defendants, the distributions are slightly different. Females under the age of 29 make up 14 percent of all cases filed against Black defendants but just 8 percent of all cases filed against Hispanic defendants. Young female defendants were 11 percent of all cases filed against white defendants.

Case outcomes by race & ethnicity

We showed in a previous section how over 60 percent of all case filings from MCPO end with at least one guilty charge while most charges within each case are dismissed. Here, we break down case outcomes by race and ethnicity of the defendant and try to understand any differences in outcomes for each group.

Of all cases brought by the prosecutor between 2017 and 2022, 38 percent ended with all charges being dismissed. When broken down by race and ethnicity, a higher share of cases (39.8%) against Black defendants ended in dismissal than cases filed against white defendants (34.2%). Cases against Hispanic defendants had a much higher total dismissal rate (65%). While there is a gap in dismissal rate between Black and white defendants, both mirror the dismissal rate for cases overall closely: around 60 percent of cases have at least one guilty charge.

In 2017, case dismissal rates varied widely based on the defendant’s race and ethnicity. Hispanic defendants had the highest dismissal rate at 66 percent while White defendants had the lowest at 32 percent. Between then and 2022, rates have declined for Hispanic defendants significantly, risen slightly for White defendants, and mostly stayed steady for Black defendants. The result is that case dismissal rates for defendants of all races has converged around 40 percent in 2022.

Why is this happening?

The higher dismissal rate for Black defendants in each year of our dataset compared to white defendants certainly raises questions. Multiple studies around the country have shown, for instance, that Black defendants are significantly more likely to be wrongfully convicted than white defendants. Additionally, Black defendants can face what's known as "Cumulative Disadvantage" in court proceedings, meaning that less desirable circumstances surrounding how someone enters the case proceeding makes it more likely they will have less desirable outcomes at the end of the process.

Understanding "why" something is happening is a core challenge in all social science research. Even when using advanced methods like statistical modeling, myriad issues arise around what variables to include or exclude and how to interpret the findings. In the course of developing this report, our team attempted several statistical models to explain why a higher percentage of cases are dismissed for Black defendants than white. These efforts were inconclusive and raised more questions than provided answers. In the process of these attempts, however, we homed in on several key considerations regarding these findings.

Offense Level Matters

Offense level is one factor potentially related to the higher percentage of dismissed cases among Black defendants compared to white. In cases where the most serious charge was a felony, all charges were dismissed 26 percent of the time among all defendants. When the most serious charge was a misdemeanor, all charges were dismissed 50 percent of the time. Simply put, the most serious charge in the case has a strong relationship with the overall outcome of the case.

White defendants have the highest percentage of cases in our dataset where the most serious charge is a felony. Over 49 percent of cases against white defendants have a felony as the most serious charge compared to 46 percent of cases against black defendants, and just 21 percent of cases against Hispanic defendants. This slight gap in the offense level of the most serious charge in the case between Black and white defendants could be related to the gap in dismissals. For Hispanic defendants, it is likely that the generally lower seriousness of the cases filed against them on average is related to their higher percentage of dismissals as well.

Many key variables are missing

Even more important than the potential relationship between offense levels are the many missing variables that could help us understand the discrepancies in dismissal rates. The criminal prosecution system is incredibly complex, and our dataset only provides a small window into the process. This narrow set of variables does not provide a full picture.

For example, there is no information in our dataset on the "quality" of cases being filed against defendants. Among the measures of case quality could be data on quality of evidence, quality of legal representation, witness cooperation, and plea deals, none of which is included in our dataset. Without information like this, it's very difficult to assess the differences in case outcomes for various groups. What appears to be an inconclusive roadblock in our analysis currently may be explained by one of these outside factors at a later date, if more data becomes available.

Spotlight: Reform efforts by MCPO

This section analyzes efforts by the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office to shift prosecutorial resources away from two of the most common low-level nonviolent offenses filed in the County: basic Marijuana Possession and Driving While Suspended.

Marijuana Possession prosecution policy change

In September 2019, new Marion County Prosecutor Ryan Mears announced that his office would “no longer prosecute certain marijuana possession offenses” in Marion County with the stated intent of “diverting resources to violent crimes, such as murder and sexual assault.” This pertained to instances where a person was possessing less than 30 grams of marijuana and “when the charge is the only or most serious charge against an adult.” There were several other conditions for a case to qualify for this policy change.

- The person could not be in possession of a firearm at the time of the offense

- The person could not be involved in growing, cultivating, trafficking, or dealing marijuana

- The person could not be driving under the influence of marijuana

- The person could not be publicly consuming marijuana

These conditions narrowed the policy change to affected only instances of basic marijuana possession with no serious aggravating factors. Those cases are filed as either Class A or Class B Misdemeanors and are characterized as “low-level” possession in this section.

The number of low-level (Class A & B Misdemeanor) marijuana possession cases filed per month declined significantly after the policy change was announced. In September 2019, the month before the change, there were 63 low-level possession cases filed. In the following month of October, there were just 8 such cases filed.

Despite the announced policy, however, there are still some cases being filed where Class A or B Misdemeanor marijuana possession is the only or most serious charge in the case and none of the other specified aggravating factors are present in the case. One possible reason for these cases still being filed are other circumstances of the case not available in our dataset. In the official policy memo, the Prosecutor Mears allowed deputy prosecutors to present reasons to deviate from this policy on a case-by-case basis.

A more detailed review of several of these cases in the State of Indiana's MyCase system did not yield answers as to why they were still being filed despite the announced policy. Although the case numbers are small (9 filed per month in 2022), this discrepancy warrants further analysis with more expansive data in the future.

The official press release from Prosecutor Mears also noted that charging these lower-level offenses disproportionately impacted communities of color. Fifty-eight percent of all low-level marijuana possession cases were filed against Black defendants before the policy change (1/1/2017-9/30/2019) in our dataset compared to 39 percent for white defendants. These cases make up 2 percent of all cases charged against Black defendants.

However, when comparing the drop in low-level marijuana possession cases among Black defendants to white and Hispanic, Black defendants had a smaller rate of decline in case filings after the change. Cases filed against Hispanic defendants were nearly entirely eliminated while cases against white defendants declined by 90 percent. Cases against Black defendants declined by 85 percent, a significant amount, but not as great of the decline as experienced by other groups.

Policy Impact

Overall, the policy change had a significant impact on reducing case filings for all racial and ethnic groups in our dataset. The number of low-level marijuana cases filed per month went from over 77 to just 9 per month. Despite case filing rates not declining as much for Black defendants compared to white, the number of these cases filed against Black defendants went from 45 filed per month to only 7. Questions remain about the cases that are still being filed after the shift in policy, but the actions of the prosecutor's office do seem to be achieving the general stated intent.

.

Reducing charges for "Driving While Suspended"

In 2022, the Vera Institute of Justice estimated that nearly 120,000 people in Marion County had a suspended license. Driver's licenses can be suspended for a number of reasons in Indiana, including failure to pay a traffic ticket, the most common reason for a suspended license according to MCPO.

Driving While Suspended was the most common charge filed in our dataset. Over 10 percent of all cases filed by MCPO between 1/1/2017 and 8/23/22 had Driving While Suspended as the lead charge, representing nearly 15,000 cases.

Recent research from the University of Michigan Fines & Fees Justice Center showed how people experiencing poverty are more likely to have their license suspended due to unpaid fees. The paper also stated that those in poverty can enter a cycle of snowballing debt, where an initial suspension leads to repeat offenses and further fines. For those beginning in an already disadvantaged position in society, removing the ability to drive can reduce employment opportunities and increase the likelihood of re-offending again for driving while suspended.

Additionally, these debt-based license suspensions are more likely to affect people of color. Here in Marion County, 12 percent of cases filed against Black defendants and 11 percent of cases filed against Hispanic defendants were for Driving While Suspended compared to 8 percent of cases filed against white defendants.

In response, the Marion County Prosecutor's Office created "Second Chance Workshops" where those with suspended licenses can work with attorneys to waive unpaid fines and restore licenses. According to the Vera Institute, over 2,000 people's licenses have been restored through this program. These workshops began in 2019 and the intent stated by Prosecutor Mears was to stop spending so many prosecutorial resources on cases where people "pose no threat to public safety."

Our data shows a significant decline in Driving While Suspended cases in 2020-2022 compared to 2017-2019. Driving While Suspended was the most common lead charge filed by MCPO in 2017, 2018 and 2019. In 2020 it fell to the third most common lead charge. By 2022, it was the 15th most common lead charge. This decline was similar for all racial and ethnic groups in our data.

As with case filings overall, the decline in Driving While Suspended cases began in the spring of 2020, coinciding with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decline in Driving While Suspended cases was much greater than the decline in cases overall. The average number of Driving While Suspended cases filed per month declined 93 percent between 2017 and 2022 compared to a 38 percent declined in overall cases filed per month.

Policy Impact

Efforts focused on reducing the number of people charged for driving with a suspended, whether through Second Chance Workshops or filing fewer charges to begin with, preceded a significant reduction in the number of people charged with this offense. In 2022, the average number of cases filed for Driving While Suspended was just 21 compared to over 372 such cases filed per month in 2017.

Next steps: Linkings prosecution and jail bookings data

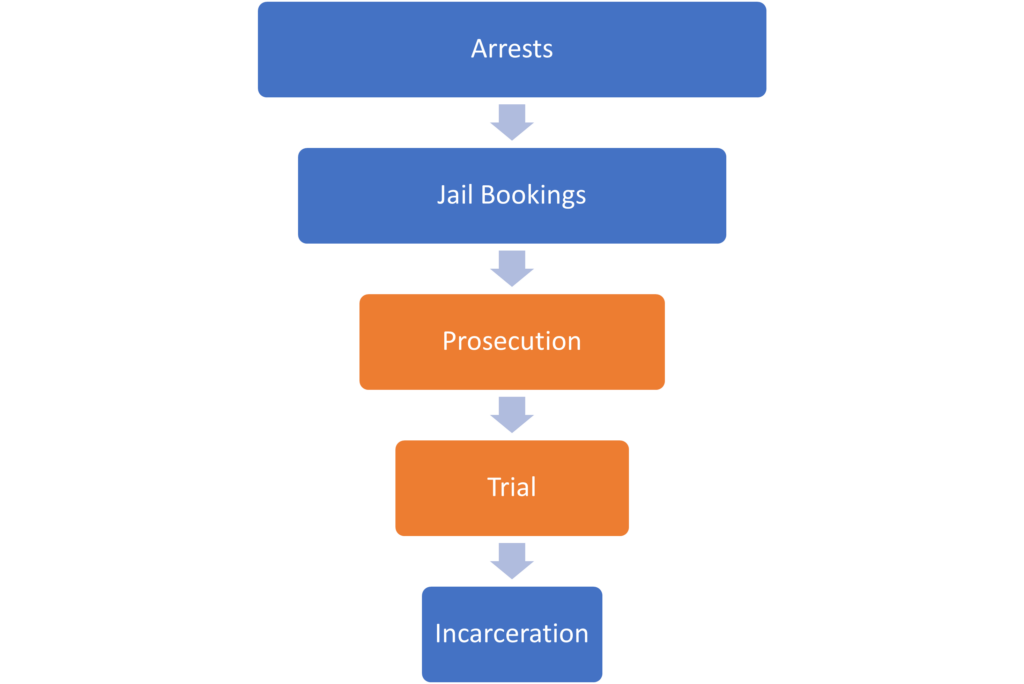

With the publishing of this report, The Polis Center has completed research on several key criminal justice topics to date: policing, incarceration, prosecution (this report), and how socioeconomic factors in childhood relate to interactions with the criminal justice system as an adult. Of course, people moving through these systems in the community do not experience them one at a time. None of these issues exist in isolation but are part of complex systems producing unequal outcomes at multiple levels. This report examines prosecutions and outcomes from trials—just two of the five stages leading to incarceration shown below.

Moving forward, The Polis Center plans to link data sources from different stages in the criminal justice process together to produce even deeper analyses than we have been able to publish to date. The following section takes the first step toward this more dynamic analytical approach by linking jail bookings and prosecution data to identify instances where people were booked in the Marion County jail, but not charged with an offense by the prosecutor. This analysis was produced by our partners at the Kheprw Institute.

Jail bookings without charges filed

The Kheprw Institute wrote a tool to download and analyze booking data from the Marion County jail system, allowing both granular and systemic analysis of trends over time. This data was then joined to the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office dataset based on the unique identifiers available for each defendant. As part of Kheprw’s mission to expand community access to civic data, they have published the source code for the tool and have provided a dataset of jail bookings on this website. Kheprw will update the booking data on a monthly basis moving forward, allowing other community members and researchers to analyze trends around who is being arrested in Marion County.

By lowering the barrier to entry around accessing arrest and booking data, Kheprw hopes to empower other community-based groups and individuals to explore trends and patterns in who is arrested in Marion County and why.

Each year slightly more than 9% of bookings, around 3,500 per year, in the Marion County jail system are listed without charges. The majority of these appear to be arrest warrants issued for probation violations, including failure to pay court fees, or for missed court appearances from prior cases. This share of bookings without charges remained mostly consistent throughout the years available in our dataset.

When an arrest is entered into the tracking system the arresting officer enters the initial charges: the reason the person was arrested. These charges are shown in the system as containing a placeholder code ('MC'). The Prosecutor's office is ultimately responsible for determining the charges pursued in court, and as those charges are filed, they are entered in the record with a different code. We looked at cases where the only charges shown had a placeholder code, which indicates that the arrestee was released from jail without the prosecutor's office filing charges.

This does not mean that the prosecutor's office did not later file charges against them, but if charges are not filed within the initial charging window they are unlikely to be filed in the future for the same incident. We analyzed bookings from 2017 through 2021 and saw a dramatic decrease in the percentage of cases with placeholder charges only. This decrease coincided with a general decrease in the number of charges filed by the prosecutor's office, so this may be explained by the prosecutor's office filing charges within the filing window before arrestees are released, but it’s also possible that police agencies have aligned their arrest priorities with the prosecutor's office priorities. It may be possible to further explain the booking-to-prosecution process by also linking these bookings to police arrest records, an example of how using datasets at multiple levels of the criminal justice process can allow for deeper analysis.

The Kheprw Institute intends on researching this issue further in future analyses and The Polis Center plans to expand our partnerships around data sharing and linking to explore criminal justice issues like this moving forward. All research from Polis and our partners can be found on our Equity Data Hub

References

- "The Cradle to Prison Pipeline", SAVI. https://www.savi.org/feature_report/equity-and-criminal-justice-the-cradle-to-prison-pipeline-in-indianapolis/

- "Who is in the Marion County Jail?", SAVI. https://www.savi.org/feature_report/who-is-in-the-marion-county-jail-exploring-length-of-stay-through-an-equity-lens/

- "Indiana has 1st illness linked to coronavirus outbreak", AP News. March 6, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/85a65282ef8f2ca99ef4fab42b7da374

- "County jails coping with pandemic", WRTV. April 8, 2020. https://www.wrtv.com/news/coronavirus/county-jails-coping-with-pandemic

- "COVID-era criminals go free: Prosecutors dismiss cases as backlog mounts", Axios. September, 28. 2021. https://www.axios.com/2021/09/28/courts-pandemic-violent-crime-prosecutions

- Vera Institute for Justice, https://www.vera.org/

- Indiana Criminal Code, https://iga.in.gov/legislative/laws/2022/ic/titles/001

- "Recent developments in Indiana criminal law and procedure", Vol. 49:1023, Indiana University McKinney School of Law. https://mckinneylaw.iu.edu/ilr/pdf/vol49p1023.pdf

- "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System", National Council of State Legislatures, May 24, 2022. https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-the-criminal-justice-system

- "The Alarming Lack of Data on Latinos in the Criminal Justice System", Urban Institute. https://apps.urban.org/features/latino-criminal-justice-data/

- ethnicolr, Python package authored by Suriyan Laohaprapanon, Gaurav Sood, Bashar Naji. https://pypi.org/project/ethnicolr/

- "Estimates of Undocumented and Eligible-to-Naturalize Populations by Sub-State Area", Center for Migration Studies. http://data.cmsny.org/puma.html

- "States Offering Driver’s Licenses to Immigrants", March 13, 2023, National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/immigration/states-offering-drivers-licenses-to-immigrants

- "Bill to allow non citizens to get driving cards in Indiana advances for first time", February 8, 2023, Kayla Dwyer, Indianapolis Star. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/politics/2023/02/08/indiana-bill-non-citizens-driving-cards-advances-senate-bill-248-senate-committee-passed/69881107007/

- "2018: Crime in the United States", Federal Bureau of Investigation: Uniform Crime Reporting. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2018/crime-in-the-u.s.-2018/topic-pages/tables/table-42

- "Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008", U.S. Dept of Justice. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf

- "Domestic Violence in Marion County Criminal Justice System – 2022", SAVI. https://www.savi.org/report/domestic-violence-in-marion-county-criminal-justice-system-2022/

- "2019: Crime in the United States", Federal Bureau of Investigation: Uniform Crime Reporting. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/topic-pages/tables/table-42

- "The Case for Decriminalizing Sex Work", January 11, 2021, Chelsea Cirruzzo, US News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2021-01-11/calls-mount-to-decriminalize-sex-work-in-the-interest-of-public-health

- "Juveniles Under Adult Court Jurisdiction - 2021 Annual Report", Indiana Criminal Justice Institute. https://www.in.gov/cji/grant-opportunities/files/Report-Juveniles-Under-Adult-Court-Jurisdiction,-2021.pdf

- "Juvenile court lacks jurisdiction over individuals at least 16 years of age committing certain felonies; retention and transfer of jurisdiction by court having adult criminal jurisdiction",Indiana Criminal Code, IC 31-30-1-4. https://iga.in.gov/legislative/laws/2022/ic/titles/031/#31-30-1-4

- "What happens after Indiana kids are charged as adults", October 17, 2022, Katrina Pross, WFYI. https://www.wfyi.org/news/articles/what-happens-after-indiana-kids-are-charged-as-adults

- "Race and Exonerations: Why Black Defendants Are More Likely To Be Wrongfully Convicted", October, 13, 2022. Gabrielle Gonzalez, Syracuse Law Review. https://lawreview.syr.edu/race-and-exonerations-why-black-defendants-are-more-likely-to-be-wrongfully-convicted/

- "Marion County will no longer prosecute simple marijuana possession, officials say", September 30, 2019, Crystal Hill and Ryan Martin, Indianapolis Star. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/2019/09/30/marion-county-no-longer-prosecute-marijuana-possession-officials-say/3818748002/

- "Memorandum: Marijuan Prosecution", September 30, 2019, Ryan Mears. https://weblive.ibj.com/lawyer/PDFs/2019/September/MarijuanaMemo.pdf

- "Prosecutor Ryan Mears halts filing of marijuana possession cases in Marion County", September 30, 2019, Marion County Prosecutor's Office. https://citybase-cms-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/db16b50030b24ea1b4f8ccf4f8d98c29.pdf

- "Driver’s License Suspensions for Unpaid Debt: Punishing Poverty", July 19, 2022, Nazish Dholakia, Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/news/drivers-license-suspensions-for-unpaid-debt

- "Driver's License Suspension for Unpaid Fines and Fees: The Movement for Reform", Unviersity of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, Volume 54, 2021. Joni Hirsch and Priya Sarathy Jones, University of Michigan Fines & Fees Justice Center. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2535&context=mjlr

- "Kheprw Data Sharing", Kheprw Institute. https://kheprw.org/data-sharing/

- "Equity Data Hub", SAVI. https://www.savi.org/equity-data-hub/