Who is in the Marion County Jail? Exploring Length of Stay through an Equity Lens

We analyzed more than 283,000 bookings into Marion County’s jails between 2013 and 2021. We used this data to discover how many people are in jail, the characteristics of those in jail, and how long people remain in jail.

This dataset spans nine years. In that time, state laws changed who was sent to local jails, state judicial policy introduced a risk-based diversion system, Indianapolis’ police force and prosecutors piloted new crisis response teams and changed how some offenses were charged, and the COVID-19 pandemic upended the criminal justice system. We examine trends over time to learn if there are changes in the jail population after these many policy changes and events.

On average, between 2013 and 2021, there were 2,257 people held in Marion County’s jails. Scroll through the timeline below to see how the jail census count changed over time, and the characteristics of those jailed daily.

Using jail booking data, we calculated who was in jail each day based on their booking and release dates, using booking dates between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2021, and release dates before March 29, 2022. These numbers capture a population omitted from the daily jail census – those who were jailed for less than one day. The booking data provides a useful look at the demographics of people in jail and the kinds of charges for which they are incarcerated.

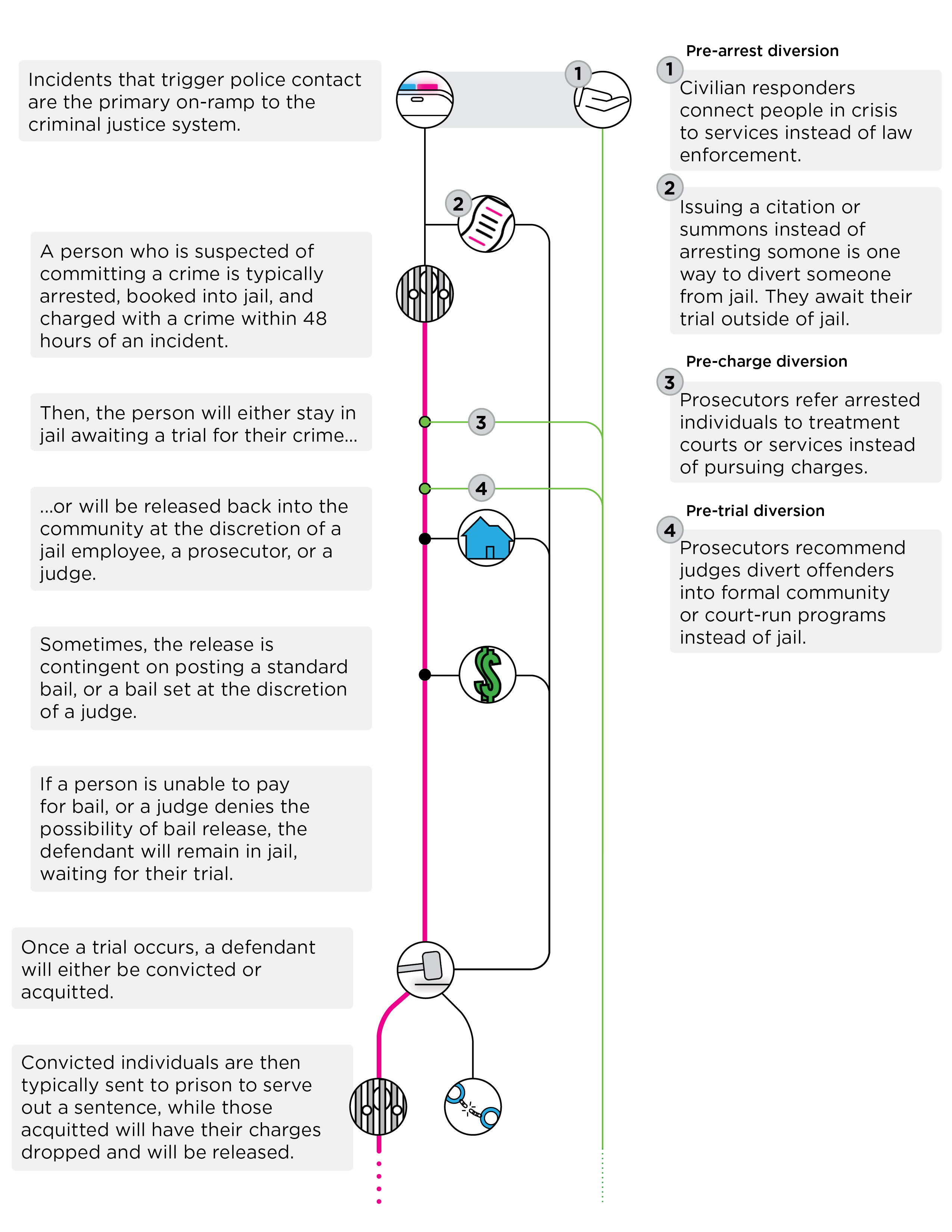

How is someone jailed?

Jail is typically used to incarcerate a person who has been arrested for an alleged crime while they await their trial. This diagram outlines the points at which a person can be jailed, can be released to await their trial outside of jail, or can be diverted into social services or programs.

Diversion Programs

Policy reforms in the criminal justice system and budgetary considerations have led to the development of a variety of informal and formal diversion programs to reduce or eliminate jail and prison time. According to the Vera Institute, incarceration has questionable value for improving public safety and has long-term negative effects on individuals and communities. Diversion programs focus on person-centered restorative practices that offer “exit ramps” to minimize contact with the legal system.

- Pre-arrest diversions are programs such as crisis hotlines or civilian responders that reduce the need for law enforcement to engage with many non-violent incidents involving drug or mental health crises. Police may also participate in pre-arrest diversion activities by connecting people with support services instead of carrying out an arrest.

- Pre-charge diversions are programs that permit prosecutors to use their discretion to refer arrested individuals to community organizations, treatment courts, and other programs instead of pursuing charges. Individuals will often still have to pay bail.

- Pre-trial diversions are also employed at the discretion of prosecutors, who will recommend to judges to divert offenders into formal community or court-run programs instead of jail. These programs often require a guilty plea, sustained time commitment, behavioral changes, and fees to offenders, but if completed successfully, their charges are dropped and their cases never go to trial. Individuals selected for pre-trial diversion will still have to pay bail and other fees.

In the case of pre-charge and pre-trial diversions, if an individual is re-arrested, they will typically face stiff penalties and will immediately face sentencing for the earlier crime for which they admitted guilt.

Assessing Eligibility for Diversion

The wide range of life circumstances and contexts for criminal activity mean that a “one-size fits all” policy for who qualifies for diversion is unwarranted. Meanwhile, the patchwork of assessment procedures – from first contact through prosecution and judgement – makes it challenging for law enforcement and criminal justice personnel to share information and develop unbiased practices for considering individuals for diversion.

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati developed and validated a standardized assessment that examines the criminal history, employment, residential stability, and drug use history to provide a reasonable evaluation of a person’s likelihood of recidivism. This research has led to the development of formal protocols in Ohio that were then piloted in some Indiana counties in 2016. Pre-trial risk assessments were adopted by Marion County in 2019 and expanded into all Indiana counties in 2020.

Indiana’s Risk Assessment System (IRAS) consists of separate assessments for different parts of the judicial and incarceration process: pre-trial, community supervision, prison intake, and re-entry.

During the pre-trial assessment, a law enforcement officer conducts a 10-15 minute interview with the arrestee. The officer then completes a scoring rubric. Higher scores correlate with higher risk of recidivism or failure to appear in court. For example, if the individual’s first arrest occurred when they were younger than age 33, that counts as one point. An arrest before age 33 is considered a risk, even if charges were dismissed or the outcome of the case was a not guilty verdict. If the individual is not employed at the time of arrest, that counts as two points, but if they are employed part-time, that only counts as one point.

The community supervision screening tool and the community supervision tool are similar, but add domains related to family, social support, and neighborhood. Neighborhoods with high crime or drug availability are considered a higher risk. If the individual’s parents have a criminal record or the individual feels they lack social support, these are also scored as risks. When risk scores are high in these community supervision assessments, it leads to more restrictive supervision. The highest risk categories require “residential placement,” which is house arrest.

These screenings have been shown to accurately identify people who are likely to commit another crime or fail to appear in court. A two-year Indiana study validated the results of assessments in the pilot counties, noting that assessment scores strongly correlated with recidivism rates among the 1,000 individuals in the study.

However, some of the risk factors can introduce bias and reinforce inequitable systems. For example, age of first arrest is not race neutral. National data from 2019 shows that Black youth were arrested at 2.4 times the rate of White youth. In Marion County in 2020, Black youth were arrested more than five times as often as White youth. Previous SAVI research on use of force data suggests that police interaction is more common in neighborhoods with high crime rates, high poverty rates, and more young black men. Neighborhood crime rates are generationally linked. According to SAVI’s Equity and Criminal Justice report, “children growing up in neighborhoods with low rates of education and high rates of incarceration, unemployment, and single-parent families are more likely to be incarcerated in adulthood.” Unemployment is also a racialized characteristic. In Marion County over the past decade, the unemployment rate for Black individuals has consistently been more than twice as high as for White individuals.

Do jail diversion programs work?

Diversion programs aim to reduce the contact of the criminal justice system with individuals, keeping people in their communities, lowering the number of individuals being incarcerated, and contributing to healing and restoration in ways that reduce the chances of future criminal behavior.

Pre-arrest diversion

Some pre-arrest diversion programs, such as Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) Program, have demonstrated success reducing contact with the criminal justice system altogether. The STAR program sends a paramedic and a mental health clinician to 911 calls that meet certain criteria. For the call to qualify, there can be no evidence of “criminal activity, disturbance, weapons, threats, violence, injuries, or serious medical needs.” A police officer is not part of the response team. After operating for six months, an evaluation found that STAR responders had never called for police backup and no arrests were made. The program’s scope may be limited, however. The evaluation estimates that around three percent of 911 calls meet the program’s criteria. In a second study, researchers found that STAR reduced arrests by 1,376 over six months.

Denver’s program was modeled after CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping out on the Streets) in Eugene, Oregon. CAHOOTS has a team of crisis-workers and medics that are dispatched to and resolve about 20 percent of all 911 calls. If an evident crime is in progress police will be called for backup, but in the vast majority of cases CAHOOTS, provides direct support and referral services that prevent unnecessary distress, escalation, and arrest by police in non-violent, often mental health and drug-related circumstances. “Of the estimated 24,000 calls CAHOOTS responded to in 2019, only 311 required police backup,” according to the Vera Institute.

Similar programs are being developed in larger cities, including Indianapolis. Mobile Crisis Assistance Team (MCAT) was implemented in the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department’s East District during a pilot period in 2017 and has since been expanded to more parts of the city. The program, emulating the CAHOOTS model, responds to calls related to drug overdoses and mental health crises and intends to reduce uniformed officer involvement in time-intensive pre-arrest circumstances and to redirect individuals into treatment facilities. The program is still young and lacks some procedural clarity, but is recognized by community leaders as an avenue to improve substance abuse and mental health crisis response. According to the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, approximately 40 percent of inmates in the county’s jails were identified in 2015 as having some form of mental illness, and there is substantial overlap between mental health and substance abuse disorders.

Crisis response programs can de-escalate and resolve these kinds of incidents before an arrest. This can keep some individuals out of the jail system altogether while simultaneously providing targeted treatment and resources. There have been calls to not only expand MCAT, but also modify the program. MCAT does not avoid police contact because the crisis response team includes a police officer. Community members have pushed for a crisis response program without an officer, and in March 2022, Mayor Joe Hogsett pledged to fund a pilot program with crisis teams that do not include a police officer “as early as the next budget in 2023,” according to the Indianapolis Recorder.

Post-arrest programs

Studies on the effectiveness of post-arrest diversion programs focus on re-arrest rates among program participants compared to their incarcerated peers. A twenty-year natural experiment conducted in Harris County, Texas determined that formal diversion programs had the potential to “fundamentally alter an individual’s trajectory in life.” Future convictions were reduced by about 50 percent, employment outcomes improved by about 50 percent, and individuals had significantly higher earnings in the subsequent ten-year period. Furthermore, the study concluded that those at the highest risk of recidivism (young Black men with at least one misdemeanor) gained the most from the programs.

Overall Impacts on Jail Population

Beyond the impact on individuals, diversion programs are also implemented as cost-saving measure for jails. According to a 2015 University of Michigan study, a year of incarceration for one individual ultimately costs approximately $70,000-$80,000 (in today’s dollars) in direct expenses, economic impacts, and future criminal behavior. Releasing individuals into pre-trial programs can substantially impact the length of time a person is incarcerated: individuals can avoid jail time before a trial as well and can complete a program in the community in-lieu of a conviction and imprisonment.

In order for diversion programs to meaningfully decrease the jail population, they need to reach people booked on felony charges. In Marion County, it is unusual for a person to be held in custody awaiting trial for the kinds of non-violent offenses that qualify for diversion programs, according to Lucy Frick, an attorney with the Marion County Public Defender Agency. According to our estimated daily jail population, 50 to 60 percent of the jail population on any given day is booked on a violent charge and over 90 percent are booked on felony charges.

SAVI estimates show that, on average between 2013 and 2021, 70 percent of the jail population was booked with a level four through six felony or A or B misdemeanor as their highest charge. Diversion programs could mean people with misdemeanors or low-level felonies avoid jail or spend less time in jail, decreasing their proportion in the jail population. As a result, jail populations would consist of a higher proportion of people in jail for high-level felonies.

Most people are in jail for low-level felony charges

Proportion of jail population in each charge level by year (daily average)

We do not find trends strong enough to confirm such a shift. People with misdemeanors make up a smaller share of the jail population than they used to (8 percent in 2021 compared to 12 percent in 2015), but the reduction mostly took place between 2015 and 2016, before MCAT or Indiana Risk-Assessment System (IRAS) began in Indianapolis. People with low-level felonies make up a higher share of the jail population than they once did (67 percent in 2021 compared to 54 percent in 2013), while high-level felonies are a lower share of the jail population (25 percent in 2021 compared to 33 percent in 2013).

Moreover, the total jail population remains relatively unchanged. On December 31, 2021, 2,202 people were in jail, which is down 18 percent from the peak in 2017. However, compared to the pre-pandemic average (2,324), the jail population has only fallen 5 percent.

The following analysis uses data from 2018 to 2021. We do this for two reasons.

- There were two periods of time with unreliable bookings data: December 15, 2013 to September 15, 2014 and January 1, 2017 to May 15, 2017. By beginning in 2018, we avoid these unreliable periods.

- One focus of our analysis is people who are jailed and have mental health or substance issues. Beginning in 2018, these data include flags or “alerts” for these issues.

Who is in jail?

The next section of our analysis addresses two questions: “Who is in jail and for how long?” and “What influences jail length of stay?” We will approach this by examining the length of stay (the number of days a person stays in jail), the characteristics of people who are booked into jail, what they are charged with, and mental health and substance-related situations that impact their experiences.

Because Marion County Jail began recording data in 2018 about the mental health and substance experiences of people in jail, this analysis utilizes jail bookings that took place between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2021. Because length of stay can only be calculated for people who have left jail, only those who have left are included in the analysis.

Between 2018 and 2021, 63,480 people were booked into jail a total of 131,000 times. While our previous discussion about the jail census over time examines relevant data about race and charges (counting each person only one time), this analysis uses booking-level data to understand length of stay. Booking-level data counts each time a person is booked into jail (counting each person multiple times). While 59 percent of people are booked into jail only once, 41 percent are booked multiple times and 8.5 percent are booked five times or more. The analysis at the booking level is valuable because it captures individuals who are underrepresented when looking at the person-level data because they have had multiple experiences in jail.

Forty-eight percent of people jailed between 2018 and 2021 are Black. This is much higher than the share of Black individuals in the overall population. In Marion County, 27% of the population is Black, according to 2020 estimates from the American Community Survey.

White and Black people have a similar rate of bookings per person (2.1 bookings per person). Hispanic and Latino people have slightly fewer bookings per person (1.4). Men are more likely than women to be booked into jail multiple times (2.1 bookings per person compared to 1.9).

Ethnicity is not reliably captured. Five percent of people who have ethnicity marked are identified as Hispanic or Latino. Only 54,000 people have ethnicity indicated (out of 63,480). Jail administrators expect Hispanic or Latino people actually make up 10 percent of the jail population and many are mistakenly identified as White Non-Hispanic.

Half of people in jail are Black, compared to 27% of Marion County population

Race of people booked into jail, 2018-2021

Three in four people booked in jail are men

Gender of people booked into jail, 2018-2021

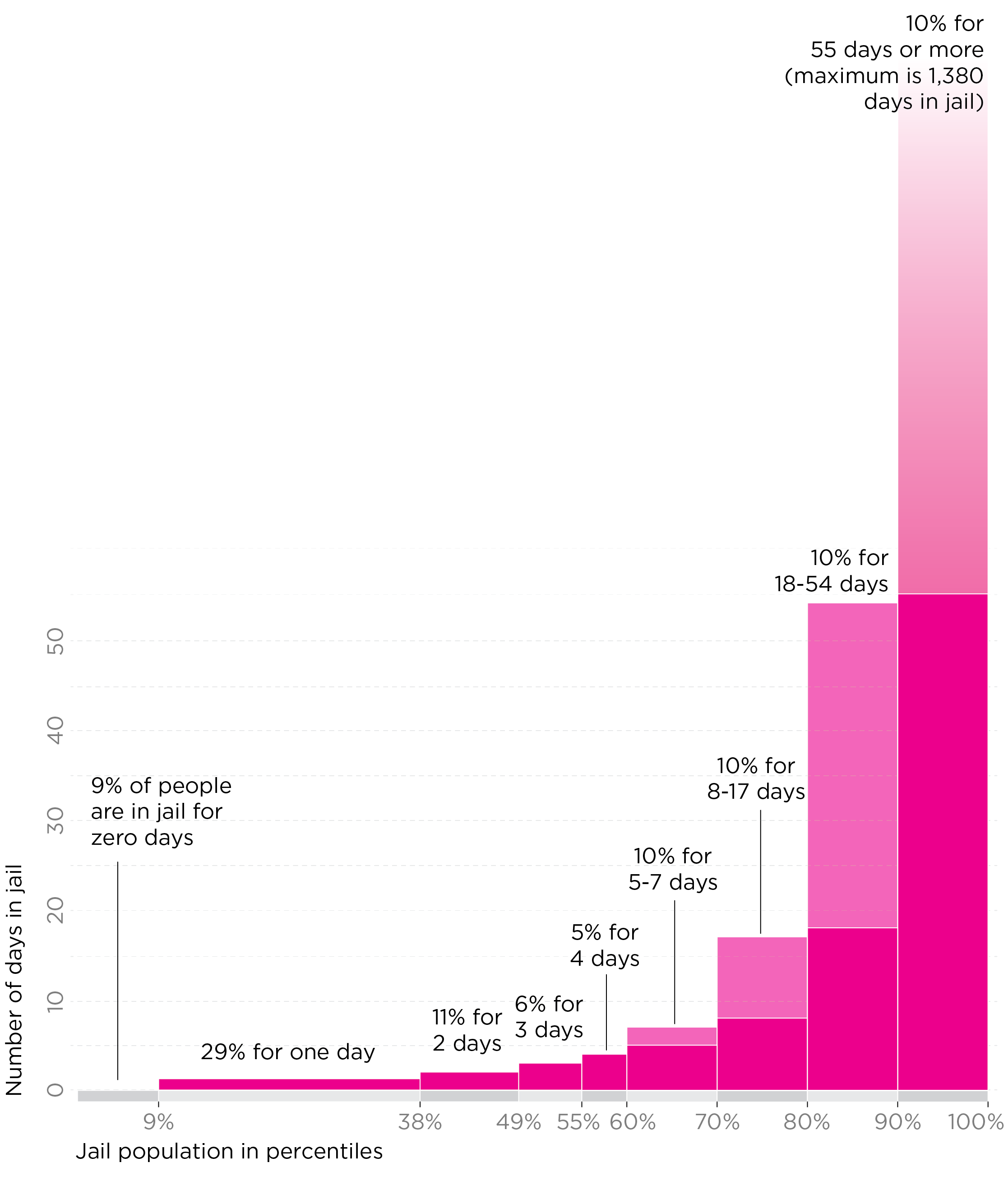

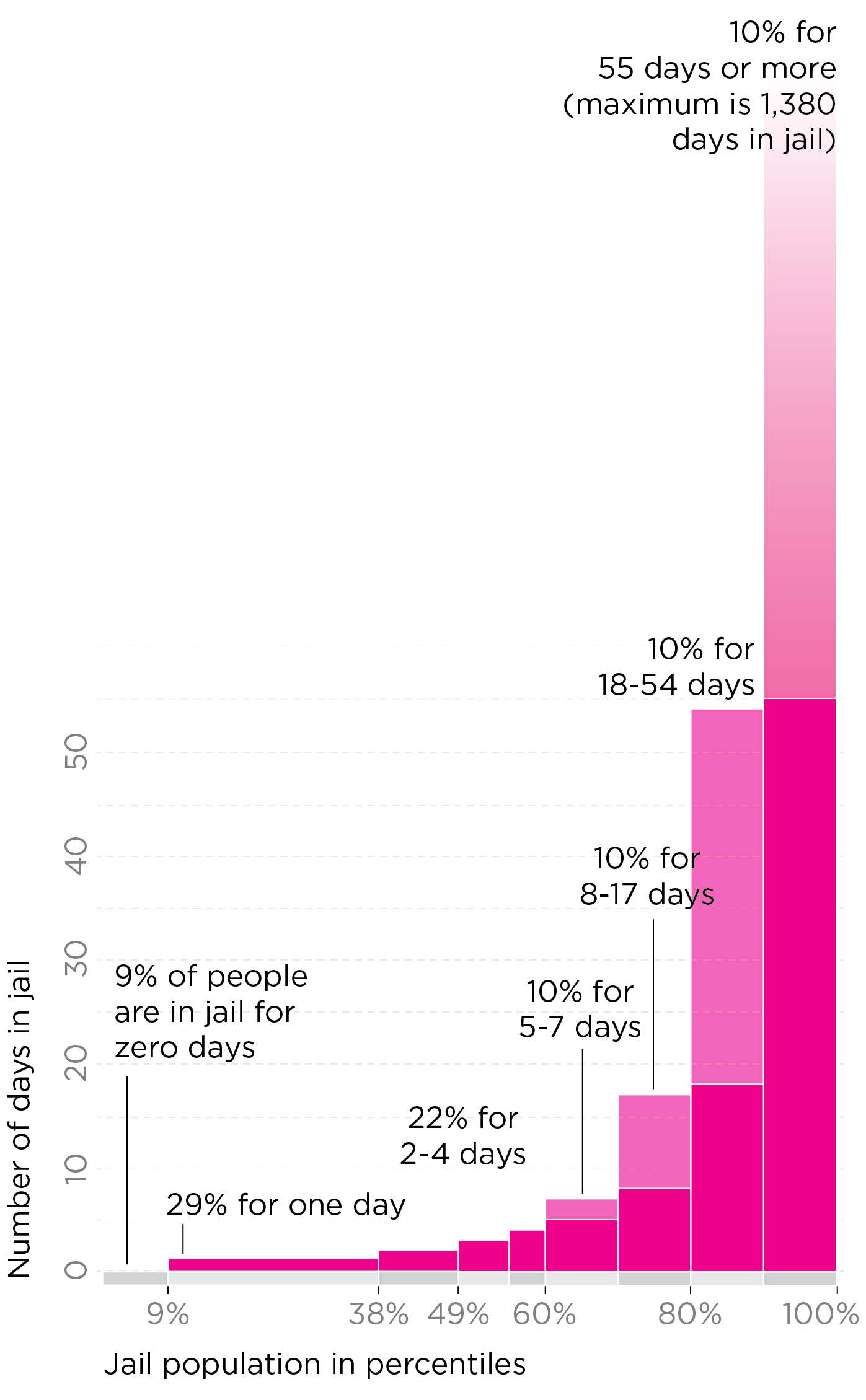

How long do people stay in jail?

Overall, from 2018 to 2021, 49 percent of bookings resulted in fewer than three days in jail: 8.6 percent of bookings lasted less than one day, 29 percent lasted one day, and 11 percent two days. Meanwhile, the length of stay at the 90th percentile of bookings is 55 days, and the maximum length of stay during this time was 1,380 days, or 3.8 years, a range of 1,325 days. These few bookings with long stays skew the average: The average length of stay is three weeks, while the median is only three days.

Half of people who are booked remain in jail for fewer than three days

Percentiles by length of stay, 2018-2021

While more than half of jail stays are short, there are a small number of exceptionally long stays that make the average length of stay deceptively large. We address this problem by using the median, or middle, value to compare groups for our statistical analysis.

Even brief stays in jail can have an impact on an individual. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, a short jail stay can cause an individual to lose a job or lose pay, and can cause hardship on families as it severs social ties and disrupts caregiving relationships. An ethnographic study by University of California, San Francisco’s Megan Comfort outlines the hardship low-level criminal justice involvement puts on a family. An arrest is estimated to make someone less likely to graduate high school. A short jail stay can even make someone less likely to vote, according to MIT’s Ariel White.

What factors relate to length of stay?

Race and gender

We examine length of stay by a combination of race and gender to understand how these might vary by a typical person with these characteristics. Of people jailed between 2018 and 2021, Black men make up a larger proportion than White men (36 percent compared to 30 percent). Black women make up a smaller proportion of the jail population than White women, (9 percent compared to 13 percent).

Bookings by race and gender

2018-2021

There are differences when you consider gender as well. For Black men, the median stay in jail is three days, while it is only one day for Black women. White women stay in jail for a median of two days, compared to three days for White men.

Women tend to have shorter stays in jail than men.

Median length of stay in days by gender and race, 2018-2021

These differences by race and gender are statistically significant, and for felonies, race and gender can be moderately strong predictors of how long someone will stay in jail. For high-level felonies, race and gender explain about 17 percent of the differences in length of stay. For low-level felonies, race and gender explain nine percent of the differences in length of stay. Race and gender are not predictors of length of stay for misdemeanors, for which they only explain 2-3 percent of variation.

A person is often booked into jail with multiple charges. To understand the level and severity of charges, we assigned the most severe charge associated with a booking as the “highest charge.”

- Infractions are mostly traffic violations.

- Low-level misdemeanors are level C and D misdemeanors. The most common offenses in this category are operating a motor vehicle without ever receiving a license, possession of paraphernalia, and operating a vehicle while intoxicated.

- High-level misdemeanors are level A and B misdemeanors, as well as some other specific categories. The most common offenses are resisting law enforcement, driving with a suspended license, and theft.

- Low-level felonies are level 4, 5, or 6 felonies. The most common offenses are theft, unlawful possession of syringe, and possession of a narcotic drug.

- High-level felonies are level 1, 2, or 3 felonies. The most common offenses are armed robbery, dealing in methamphetamine, and dealing in cocaine.

Severity and charge level

The severity of charges relate to the length of time a person stays in jail. Between 2018 and 2021, 39 percent of bookings are those for whom the most severe charge is a misdemeanor, while 60 percent are felonies. Most jail bookings are for low-level felonies (55 percent) or high-level misdemeanors (38 percent). High-level felonies (5.4 percent) and low-level misdemeanors (1.5 percent) are much less common among jail bookings. As discussed earlier in this report, this is most likely because low-level misdemeanors are cited or called to court at a later date, rather than being held in jail. Additionally, high-level felonies are simply less frequent than low-level felonies.

For most bookings, the highest charge level is a low-level felony or a high-level misdemeanor.

Bookings by highest charge level, 2018-2021

Less severe charges have shorter lengths of stay than more severe, higher-level charges. The median length of stay for bookings where the most severe charge is a misdemeanor is one day, regardless of whether the charge is a high- or low-level misdemeanor. On the other hand, there is a large difference in length of stay between low and high felonies. The median length of stay for a lower-level felony is five days, while it is 31 days for a higher-level felony. These results are not only significantly different, they are also meaningful. A booking charge moderately influences length of stay. It is important to consider this indicator when discussing booking length of stay.

Length of stay in jail is associated with charge level

Median length of stay in days by highest charge level, 2018-2021

Thirty-two percent of bookings have one or more violent charges, which as expected, are associated with statistically significant longer lengths of stay. Bookings with a violent charge have a median stay of three days longer than those without one. Even though this difference is statistically significant, violent charges are not a strong predictor of length of stay. Length of stay actually varies quite a lot within violent or non-violent charges.

Mental health and substance alerts

We also want to understand whether jail bookings associated with the person being flagged for a mental health- or substance-related situation is related to length of stay. Doing so will help us understand whether there is a proportion of the population that could have received a medical or behavioral health intervention rather than a jail booking.

Between 2018 and 2021, 21 percent of jail bookings are associated with an “alert,” that is, a flag related to a mental health- or substance-related situation or event. Across all bookings, 16 percent have a substance-related alert, while 7 percent have a mental health alert. Mental health alerts include segregation for mental health reasons (6.8 percent of bookings), which includes suicide-related segregation (5.1 percent of bookings).

One fifth of bookings have a mental health or substance use alert.

Percent of bookings with alert, 2018-2021

There is a significant difference in length of stay between bookings with and without each of these alert types. Among those with any type of alert, the median length of stay is six days, which is four days longer than those without an alert. Bookings with individual alerts have varying median lengths of stay compared to bookings without those alerts. Those with a substance-related alert have a median length of stay that is three days longer than those who do not. Those with a mental health alert have a median length of stay a week longer than those that do not. The largest difference is among those with a suicide segregation alert. These bookings have a length of stay that is 10 days longer than bookings that do not have this type of alert.

While people with mental health conditions are disproportionately likely to be booked into jail, being in jail may cause an existing mental health condition to become more acute, requiring treatment or other behavioral health responses. This could increase jail length of stay to protect an individual from harming themselves or someone else.

When someone is booked for a felony charge, the presence of an alert is a moderate predictor of how long they will stay in jail. For high-level felonies, the presence of an alert explains 17 percent of the variation in length of stay. For low-level felonies, alerts explain nine percent of length of stay. For misdemeanors, the relationship is weaker. Alerts explain only three percent of length of stay.

When someone is booked with a mental health or substance alert, they tend to stay in jail longer.

Median days in jail for bookings by presence of alerts, 2018-2021

Length of stay may be longer for those with a mental health alert because they tend to get booked for more severe charges. People who have never received an alert are booked on low-level felonies 49 percent of the time, compared to 65 percent for people who have received an alert.

Even with similar charge levels and severity, people with an alert are often in jail longer. The median length of stay for people with an alert is 46 days for a high-level felony and seven for a low-level felony. For people without an alert, the median length of stay is 27 days for a high-level felony and 4 days for a low-level felony.

This pattern does not hold for misdemeanors. The median length of stay for misdemeanors (high- or low-level) is one day, whether the individual has received an alert or not.

People with a mental health or substance alert are booked for a felony more often than people without an alert.

Percent of bookings by highest charge level and presence of alert (people with an alert associated with any booking)

People with an alert stay in jail longer than others when booked for a felony.

Percent of bookings by highest charge level and presence of alert (people with an alert associated with any booking)

To summarize our analysis of length of stay, the severity of charges is predictive of how long someone will stay in jail. For those booked on felony charges, gender and the presence of an alert are also associated with length of stay.

Disproportionalities in length of stay are important to address because they may indicate inequities in the criminal justice system. Black males face the greatest disproportionalities in length of stay, as their length of stay is 10 days (about 1 and a half weeks) longer than everyone else. At the same time, bookings associated with mental health-related alerts have greater lengths of stay than those that do not. Policies that decrease the stay of people with alerts or diverts them from the jail entirely will decrease the jail population.

Just as the previous analysis defined highest charge, this analysis defines the offense associated with that charge as the “lead offense.” Sometimes, multiple offenses tie for the highest charge. In this case, we consider the offense listed first as the lead offense.

Lead offenses and length of stay

Twenty-six offense types account for 75 percent of all bookings since 2018. The most common are theft, operating a vehicle while intoxicated, and possession of methamphetamine. These offenses are generally charged as high-level misdemeanors or low-level felonies. One fourth of bookings have lead offenses related to drugs or substances (excluding driving while intoxicated). For three percent of bookings, the lead offense is related to dealing substances. Possessing substances accounts for 19 percent of bookings.

Most of these bookings result in short stays in jail, but offenses that are less common can contribute significantly to the jail population if people stay in jail longer after being arrested. To understand this, we use a statistic called total bed-days. A bed-day is equivalent to one person in jail for one day. If 100 people are in jail for one year, that is 36,500 bed days.

Theft again tops this list of lead offenses, with 204,000 bed-days (7 percent of total bed-days). Possession of methamphetamine and auto theft have the next highest number of bed-days. Almost all the bed-days are from felonies. Misdemeanors lead to short jail stays, therefore they contribute little to total bed-days.

Substance-related offenses (excluding driving while intoxicated) account for 28 percent of total bed-days. Charges related to dealing substance make up 10 percent of bed-days, and charges related to possession account for 17 percent of bed-days.

Policies seeking to limit interaction with law enforcement and decrease the number of people involved in the carceral system should focus on offenses that most often result in bookings. Policies seeking to lower jail populations should focus on offenses that contribute the most to total bed-days.

Most common reasons people are arrested and booked

Bookings by lead offense, 2018-2021

Offenses with the highest total bed-days

Total bed-days by lead offense, 2018-2021

Policy Implications

The reasons many people are booked into jail unnecessarily is related to both the misuse of jails to keep our communities safe, and a lack of appropriate responses and solutions to some of the conditions that cause people to be jailed in the first place. Jailing those who are not a threat to themselves or others while waiting for their day in court disrupts the fabric of families and our communities. Sending people to jail who were arrested for situations related to mental health or substance use disorders, experiencing homelessness, or the conditions of poverty do not receive the support they need to live safe and stable lives.

To divert these people from the Marion County Jail, thereby reducing its jail population, the following actions hold promise:

- Invest funds in clinician-led support teams that address emergent situations that do not require law enforcement presence because no crime is in progress, such as when someone needs behavioral support and case management services. Pair clinicians with peer specialists who can provide individualized support from a vantage point of personal experience.

- Expand implementation of cite-and-release practices, which became more common during the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic as a means of controlling the spread of disease by controlling the jail population. Utilize them as a means of minimizing the impact of the carceral system on people, families, and the fabric of Indianapolis communities until a conviction (if any) and sentence are received.

- Continue offering the pre-trial risk assessment program as an option for people who cannot afford bail to avoid and shorten disruptive jail stays.

- Collect Marion County Jail data on a variety of demographic indicators that are important to responding to inequities related to unnecessary jailing based on non-violent offences and situations for which jail is not the best option. This includes data on race and ethnicity that is more nuanced than the binary “Black” and “White” to represent people of different ethnicities and of more than one race. There is also a need for more nuanced reporting of data related to the mental health and substance-related experiences of people in jail. Data about their mental health conditions is key to understanding the clinical services needed to pinpoint pre-arrest diversion services, address the needs of people while in jail, and reduce the likelihood of being jailed again in the future. Data related to the use of substances including substance use disorders is important to ensure that appropriate medical and behavioral health support and harm reduction practices keep people healthy, safe, and supported both while in jail and upon release. This is particularly important given the pandemic-related resurgence of overdose deaths, including those related to opioid use.

- Develop, implement, and maintain data collection instruments and systems that make possible the accurate and reliable analysis of demographic data about justice-impacted people in Indianapolis. Increase the capacity of all units within the system to be able to respond to the trends revealed by the data.

No call for addressing inequity in our community is complete without the ability to measure it and assess change over time. We cannot demonstrate the specific ways and extent to which inequity exists in crisis response and the criminal justice system without accurate and complete data about those affected, and the ability for policy researchers to access and study that data. Existing support within Marion County’s criminal justice system must be tapped expand activities related to gathering and recording data on race and ethnicity. This will allow us to better understand which populations are most impacted, and thus, where resources need to be directed to address and prevent inequities.

Notes

Analysis of booking data is based on anyone booked during the analysis period, so it excludes anyone who was already in jail at the start of the analysis period. These people are represented in the total jail census.

“People with an alert” are individuals who were flagged with a mental health or substance abuse alert during any of their bookings. We assume that officers are likely to undercount the number of people with mental health or substance abuse issues, rather than overcount. Therefore, in some cases, we use this measure of people with an alert

When we estimate the jail population using bookings data, we deal with several issues. Bookings data was unreliable from December, 15, 2013 to September 15, 2014 and from January 1, 2017 to May 15, 2017. We do not include data from these periods. The initial period (the first few months of 2013) shows an artificially low number of people in jail, because it excludes anyone in jail who was booked before January 1, 2013. Similarly, the final period (the last few months of 2021) shows a discrepancy between the official jail census and our estimated census. We still show these periods and focus on showing each group as a percent of the total jail population. The total jail census avoids these issues.

Thank you to Jennifer Montez-Luna of the Marion County Sheriff’s Office for her assistance accessing and understanding the data. Thank you to Taylor Johnston, fellow at The New York Times, for her assistance with data visualization. Thank you to Lucy Frick of the Marion County Public Defender Agency for her insights into the policies and procedures of courts and prosecutors.

A special thank you to Faith in Indiana, who was a partner on this initiative. It was funded through the Catalyst Grant Program, a collaboration of the Microsoft Justice Reform Initiative and the Urban Institute.