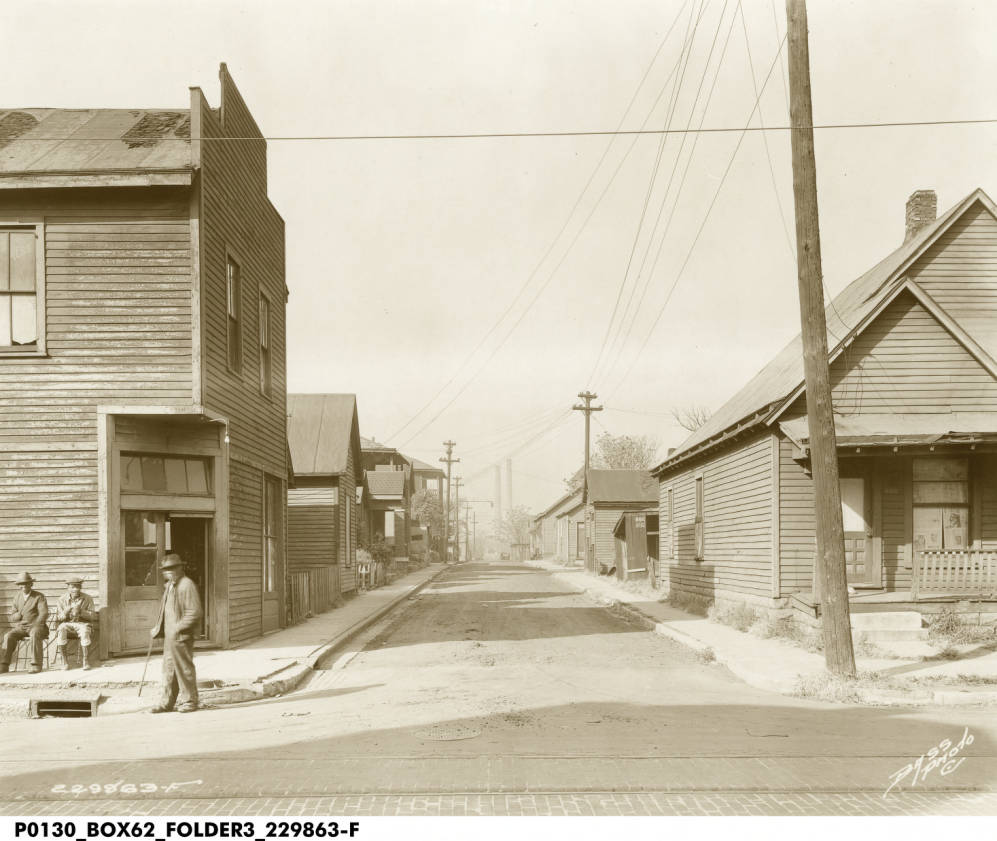

On the border between Willard Park and St. Clair Place, Michigan Street near Jefferson and Beville Avenues carries the ghosts of its former heyday as a center of neighborhood retail. One and two-story commercial buildings indicate that these blocks were once what city planners call a “neighborhood node,” a walkable, mixed-use center of activity. Fading painted siding covers up what were once handsome brick buildings. It was the kind of place that “placemaking” and “redevelopment” efforts are currently attempting to regenerate through programs like Great Places 2020.

The decline of this place is tied up in big economic and demographic trends like suburbanization, white flight, globalization, and consolidation. And as planners, cities, and communities struggle to revitalize such places, there are still unanswered questions and unresolved tensions. How do communities revitalize these nodes in ways that benefit the people of color that have moved here in recent decades, rather than catering to or attempting to attract white residents, some of whom are reversing the white flight trends of a few decades ago? How can redevelopment support small businesses in the area who have little financial and social capital?

A Neighborhood Node

Scroll through the images to compare Michigan and Jefferson in 1942 and 2019.Swipe left to explore the block.

Grocers, Taverns, and Pet Shop

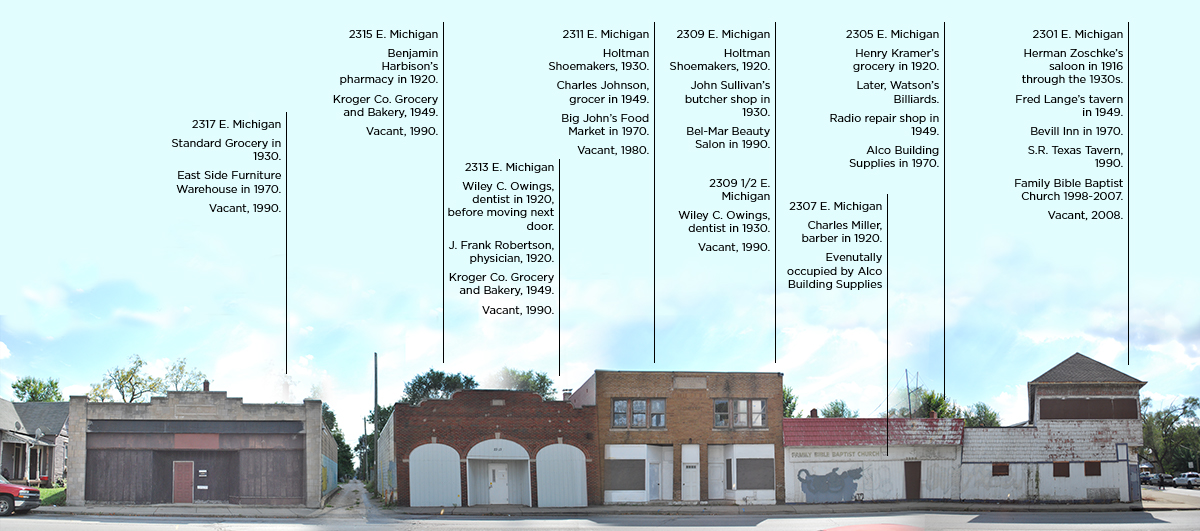

Thanks to archives of the R.L. Polk city directories, we can discover what this block felt like and who the tenants and proprietors were. We will highlight the history of some of the commercial buildings from Hamilton Avenue to Jefferson Avenue and on to Beville Avenue.

2101 E. Michigan Street. Edward C. Remmetter ran a pharmacy at this location in 1920. Remmetter once partnered with W.C. Freund, who ran Highland Cut Rate Pharmacy at the location where King Dough now stands. (Joan Hostetler of Indiana Album had a piece about this location over at Historic Indianapolis.)

For many decades after, this property would be a pet shop. In 1949, Earl J. Metz ran an aquarium supply store here, and by 1960 this was Wilson’s Aquarium and Pet Shop. In 1970, this was The Fish Bowl Pet Shop, which would remain here until after 2014. Animal Control found major violations and issued hundreds of citations to the owner in 2014, but the owner’s niece reopened the business briefly at the behest of her great-uncle and the neighborhood.

2129 E. Michigan Street. This was an auto repair shop, owned by the Luther brothers in 1920 and Orville Humes in 1930. In 1949, a physician and a dentist worked out of this space.

2131 E. Michigan Street. This was New’s Food Products Company in 1949. A 1941 Indianapolis Recorder advertisement explains that they sell wholesale restaurant and hotel supplies.

2133 E. Michigan Street. In 1920, the Soltau Brothers ran a grocery store here. The store was robbed of “several dollars in change” in 1917, according to the Indianapolis News.

Swipe left to explore the block.

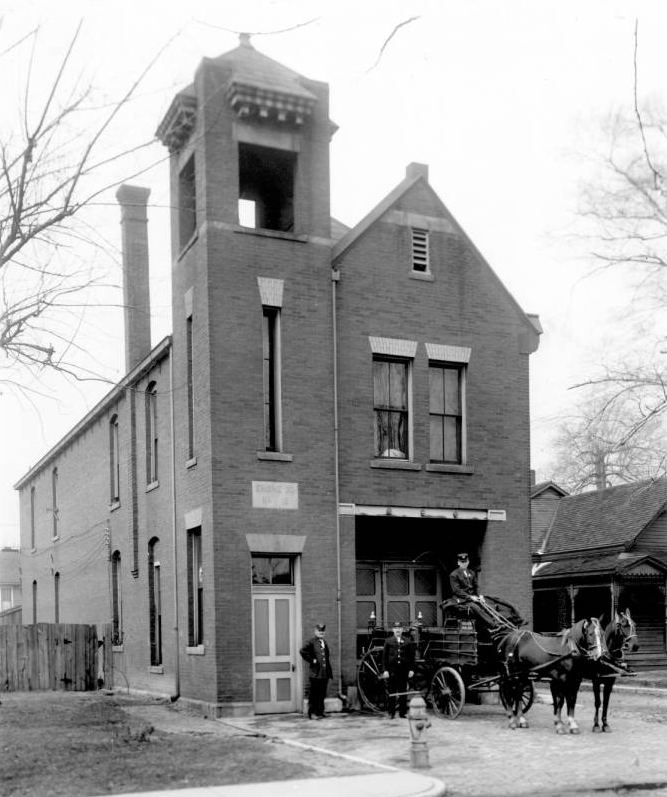

Hose C0mpany 20 of the Indianapolis Fire Department worked out of a fire station at 352 N. Beville. This lot is now a neighborhood park.

Photo: Indiana Historical Society. View Source

According to fire department records, this station was built by A.O. Despo in 1895 for $4,625. The first electric lights were installed in 1901.

Indianapolis Firefighters Museum Collection, Digital Indy, Indianapolis Public Library. View Source

2301/2303 E. Michigan Street. In 1916, Herman Zoschke ran a saloon out of the corner property. (Though by 1919 he is listed as selling only soft drinks, as prohibition approaches. Wink.) Zoschke still owned the establishment when prohibition was ended in 1933. The following year, it was listed as a restaurant. It would remain a tavern for several decades, eventually become the Beville Inn.

In 1998, Family Bible Baptist Church acquired the property and moved from the neighboring building. They moved to New York Street nine years later.

2305 E. Michigan Street. In 1920, Henry J. Kramer owned a grocery shop here. It was later a billiards hall run by Robert Watson.

2307 E. Michigan Street. Charles W. Miller had a barbershop at this address in 1920, though by 1930 he had moved his shop down the block. Raphael Kauffman, a tailor, replaced him as a tenant. Kauffman’s store would remain open on these blocks for several decades, though it moved west of Jefferson Ave. at one point.

2309 E. Michigan Street. Holtman Shoemakers, whose name is carved in limestone above the building, called this storefront home in 1920. In 1930, this was a butcher shop run by John F. Sullivan.

2309 1/2 E. Michigan Street. Wiley C. Owings owned a dentist’s office at this location in 1930.

2313 E. Michigan Street. Owings had previously run his dentistry practice from this location, after moving from the southeast side. His former location, at 1725 Olive Street, was demolished in 1972 to make way for Interstate 65.

J. Frank Robertson, a physician, was also located in this building in 1920. His parents, Methodist ministers, lived in Irvington at 65 N. Ritter Avenue, according to Vintage Irvington. A Methodist newsletter informs us that his mother fell ill in 1914, but she was “privileged with the constant skill of her son.”

By 1949, this was a Kroger Company Grocery and Bakery, competing with the Standard Grocery Company just across the alley.

2315 E. Michigan Street. This was the location of a drugstore run by Benjamin C. Harbison in 1920. Harbison seems to have moved his store a few times or owned several locations. In 1923 he opened Harbison Pharmacy at 2830 Clifton Street. And in 1918 his store at 10th and Beville was burglarized. The culprit stole two dollars.

2317-19 E. Michigan Street. By 1930, this was the home of a Standard Grocery Co. store, a common grocery chain in Indianapolis.

2325 E. Michigan Street. Alice Brennan had her beauty parlor in this storefront in 1930.

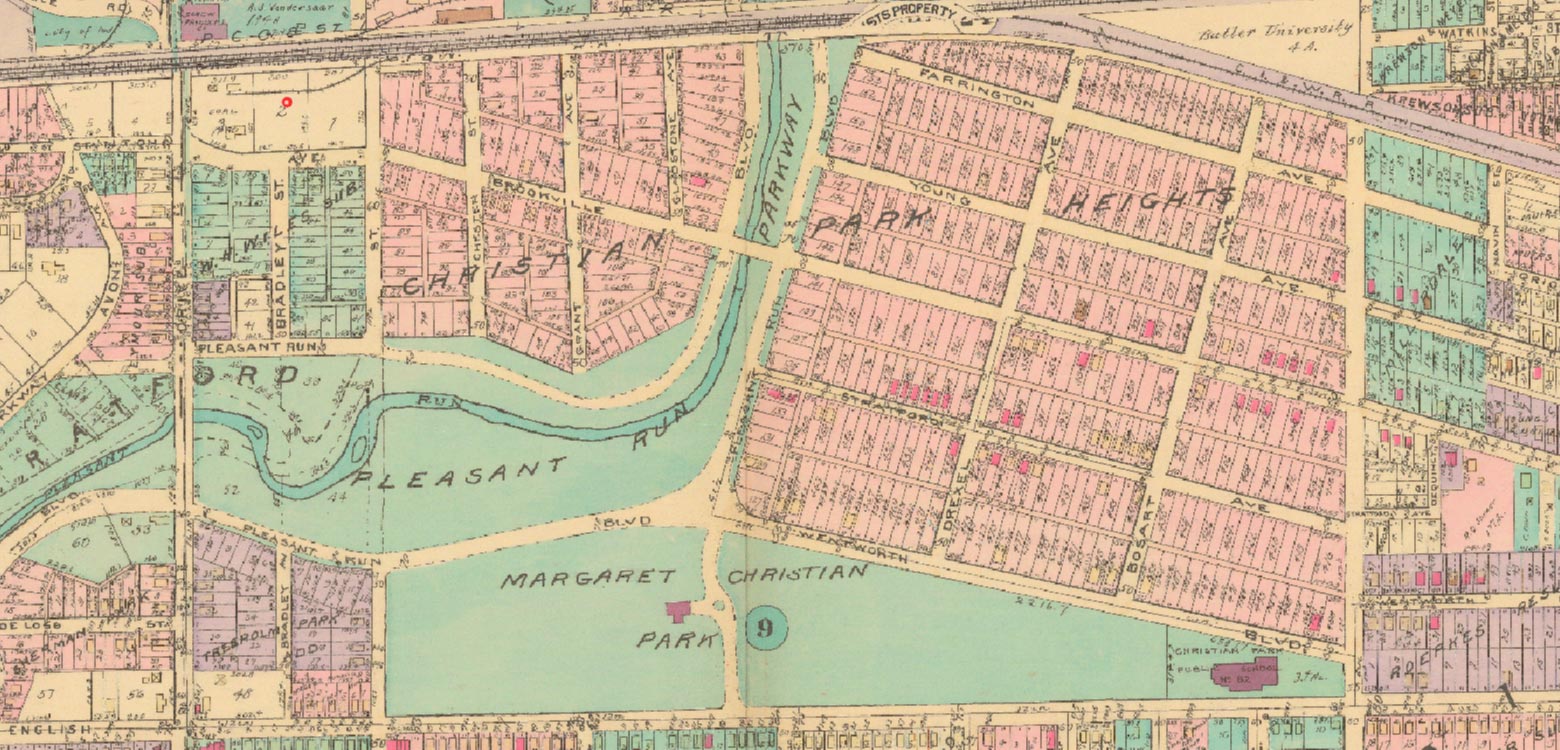

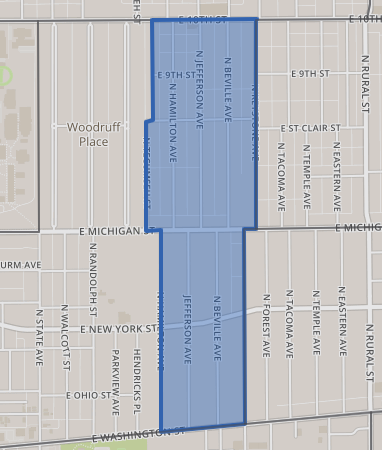

Tract 3547.00 contains parts of Willard Park (south of Michgian Street) and St. Clair Place (north of Michigan Street). In 1940, this was tract 51, but because its boundaries have not changed, you can make reliable comparisons between historic and current census data.

An interactive dashboard with data about Willard Park/St. Clair Place.

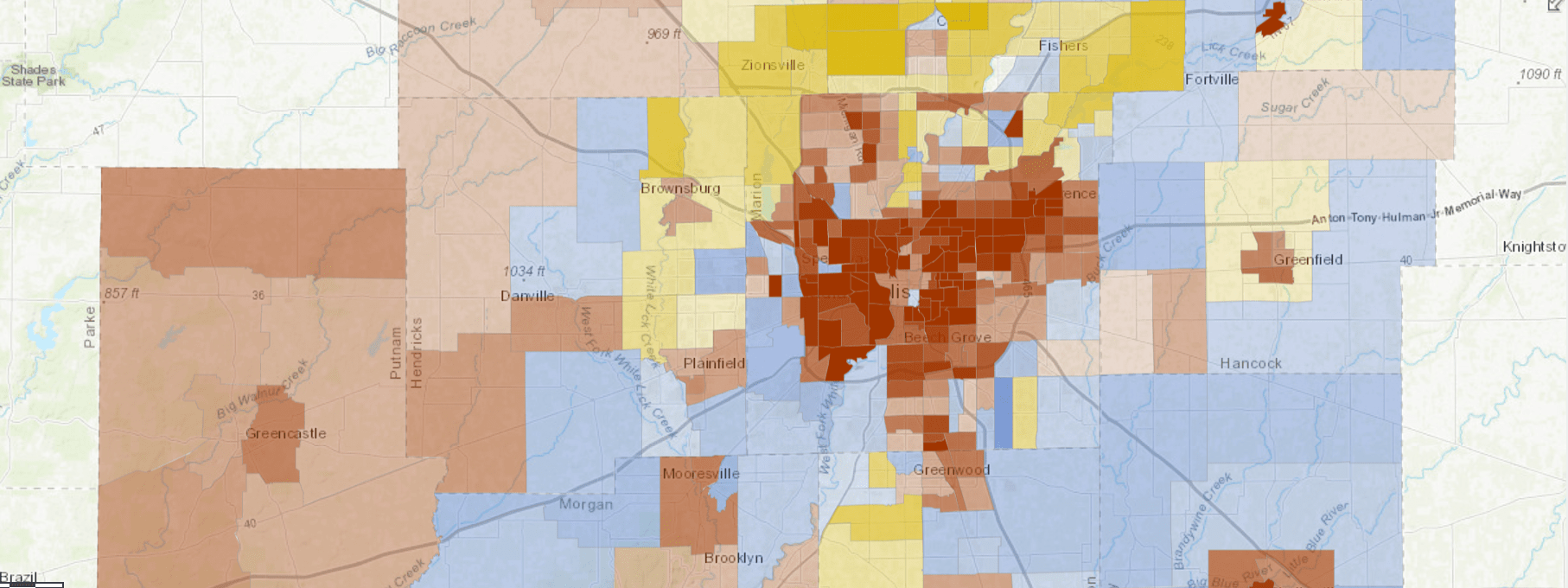

Demographic Changes Contributed to Decline of Small Businesses

Photographs of a once-bustling block can stir nostalgia for a bygone era. But it is crucial that we understand what the full character of this era was, who won and who lost in the neighborhood’s heyday, and who participated in the forces that changed this neighborhood so drastically. Put simply, the population decline that drastically undercut the market for these small businesses was driven by white flight. And the new retail models of consolidated chains with larger footprints, big parking lots, and more selection and value worked well for those who were moving to the suburbs or shareholders who owned a stake in these businesses.

There are still retail jobs in our region, but they have followed wealthy white households to the suburbs. Marion County lost thousands of retail jobs between 2002 and 2015, while suburbs built since 2000 gained 12,000 retail jobs (according to LODES data). And of course, these jobs do not pay well. The average retail worker in our region earned $456 per week in 2017. And retail establishments have often consolidated into chains, rather than businesses owned by neighborhood residents. In 1940, there were 98 proprietors of businesses who lived in the neighborhood.

Population has fallen drastically since 1940

Population by year

Despite declining white population, population of color is increasing

Population over time by race

Demographic data for this area is for census tract 3547, which in 1940 was called census tract 51. They share the same boundaries, and therefore valid comparison can be made over time.

This area exhibits the familiar pattern of population decline since the middle of the century. However, the is strong population growth among people of color in recent decades. There are 3,300 fewer white residents here than in 1940, but nearly 1,000 more residents of color. The neighborhood is much more diverse than in 1940, when only two residents were people of color. The neighborhood is now 65 percent residents of color.

Fewer people make it harder to run a small business in this area. But the economic conditions endured by the current residents mean that there is little disposable income to support such businesses.

In 2017, the median household earned $27,000, about half of the median income for the region. And since 2010, low-income households in the neighborhood have not fared well. The average income for the bottom 20 percent of households fell to only $3,276 per year, while for the top 20 percent incomes nearly doubled to $47,465. These reflects changes in household incomes as well as the kind of households that have moved into the neighborhood. Whereas in 2010 there were only 11 households that earned $75,000 or more, there are now 72 such households.

Incomes rising for top-earners, falling for bottom 20 percent

Average household income for each quintile, 2017

In 1970, one-in-three households were high income. Now one-in-three are very low income.

Approximate income distribution. Click to toggle between 1970 and 2017.

Income distribution has changed drastically in this neighborhood since the middle of the twentieth century. In 1970, high incomes were common in the neighborhood. In 2017, very low incomes are the most common.

Most households were at least middle income in 1970, earning $33,900 (in 2017 dollars) or more. Today, only 39 percent earn $35,000 or more. A quarter of households earn $15,000-$34,999, and over a third of households earn less than $15,000.

In order to revitalize neighborhood retail nodes like this historic area, our residents have to have the financial means to support local businesses. And as long as 316,000 people in our region are low-income, black households earn half what white households earn, unemployment for black workers is almost three times higher than for white workers, and poverty rates are 2.6 times higher for people of color than for white people, communities of color will struggle to obtain neighborhood amenities that were once common place.

See How Your Neighborhood Has Changed

Find more interactive content from our series on neighborhood change.

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.